Copyright © Hans Högman 2020-07-16

The Old Agricultural Society and

its People - Sweden

In Swedish agricultural society, especially during the

18th and 19th centuries, one didn’t really speak

about the family on the farm but rather about the

people on the farm. The people on the farm

included the farmer and his family, of course, but

also the hired hands: pigor (pl.) and drängar (pl.).

Piga was the term used for a female employee, i.e.

a maid.

Dräng was the term used for a male farmhand.

Farmhands and maids could be either young

people who took positions as hired hands until they

could get enough money to get their own place or

elderly people who hadn’t been able to get their

own place as farmers or tenant farmers.

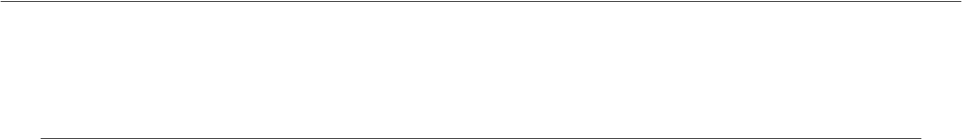

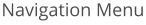

The image to the right is

from the kitchen in

Kvekgården farm near

Enköping town (C).

Kvekgården is a today

an old homestead

museum. Photo Hans

Högman, 1992.

At most Swedish farms there were seldom more

than 10 persons. It was difficult to feed more than

that.

A farmer often hired farmhands and maids if he

and his wife were young and had small children.

When the children grew up and could help out with

the work on the farm, the farmer really didn’t need

the help of farmhands and maids or at least not as

many.

Farmers usually didn’t have many children. They

married late. Women were often 25 years old or

more when they married, and men were around 30

years of age. It took a while before they could

afford a farm. However, traditions were different in

the various parts of Sweden.

Tenant farmers (torpare/landbo) and the backstuge

people didn’t have any farmhands or maids. They

themselves worked for others and couldn’t afford

to hire anyone else. These groups often had to

send their young ones away to take positions as

“lillpiga” (a young girl serving as maid) or “lilldräng”

(a young boy serving as farmhand) to a farmer to

earn their own living.

Marriage

In the agricultural society of former days, it wasn’t

love that determined who one married. The family

of the person one married and the size of their

farm were much more important.

You don’t have to go further back than to the

beginning of the 1900s to find that it was

unthinkable for a married woman in Sweden to be

outdoors without any coverage of her hair. A

woman couldn’t go out without covering her hair

with a hat or scarf etc. This custom was very long-

lived in the countryside.

There is a story – true or not - about a woman a

long time ago in a small country village who was

outdoors in the early morning doing an errand. She

was only wearing her night chemise and hadn’t

covered her hair (and in those days the countryside

women didn’t use any underwear because it was

too expensive). Even though it was early, she met a

neighbor. Quick-witted as she was, she lifted her

chemise so that the hair was covered. It was

obviously more important to cover the hair then

the rest of the body.

Undantag

Undantag was a system of caring of elderly. In the

old agricultural society the old ones on a farm were

placed in “undantag”. This meant that when an old

couple signed over their farm to one of their

children (to a son, for example), the old couple

could stay on the farm – usually in a smaller cottage

that was provided for them. This smaller house or

cottage was called undantagsstuga. The older

couple signed a contract

(undantagskontrakt/födorådskontrakt/fördelskontrakt)

with the child who took over the farm which

stipulated that the old ones would receive a certain

amount of firewood, grain, hay, milk etc every year.

This was called födoråd and the old people taking

benefit of this were födorådstagare.

This system was also used when someone else

than a family member bought a farm from an

elderly couple.

Undantag (exemption) or undantagskontrakt

(exemption contract) means the right of the seller

to retain for his remaining lifetime the right to use a

small dwelling or a small area of land, that is

exempt from the buyer's right to dispose of the

transferred property. The beneficiary retains this

right even if the property was resold.

Födoråd was a personal right which meant that the

födorådstagaren (the recipient) received from a

farm property certain goods such as daily needs of

milk, potatoes, or hay.

Inhysehjon

Pigor (maids) and drängar (farmhands) who

perhaps had worked all their lives on a farm could

stay on the farm when they got older and couldn’t

work any more, as inhysehjon. There were no

social welfare programs or homes for the elderly

back then so this was an early way of providing

welfare: they took care of each other.

An inhysehjon was someone in need of help from

the society – public care, i.e. poor, sick, infirm

elderly etc.

However, not everyone in the countryside lived on

farms. There were many poor, disabled, and sick

people who had to survive on what the farmers

could give them. It was a kind of charity.

Auctions of Poor Children

In the middle of the 19th century there even were

auctions of poor children as well as infirm

elderly to farmers who made the lowest request

for compensation for taking care of them. It was

the local village council, the socken, which held these

auctions. Very often the children were submitted to

hard work on the farm they were placed at. This

was a kind of early foster-home placement. The

auctioning of poor people continued until 1918

when the practice was abandoned.

Drängar and Pigor

Drängar (pl.) and pigor (pl.) were employees

working on farms. However these terms once also

referred to unmarried sons and daughters who

were still living and working at their parents’ farm.

This meaning is still used in Denmark as terms for

boys and girls. In Sweden, employees at farms were

called tjänstrdrängar and tjänstepigor to distinguish

them from the sons and daughters on the farms.

Tjänstepiga could be translated into servant “piga”.

Collectively they were called “tjänstefolk”.

However, later on, the terms dräng and piga were

only used to refer to the hired people on farms.

Other words used when referring to farm

employees, besides tjänstefolk, were tjänstehjon

and legohjon.

Dräng

Drängar (pl.) were, in other words, male farm

laborers doing heavy work on the farm. They were

usually unmarried and hired for a year at a time.

Their employment was regulated under a law called

tjänstehjonsstadgan.

On larger farms, farm laborers lived in special

quarters for farm hands. This could be a room on

the farm (drängkammare) or a separate building, a

so-called drängstuga.

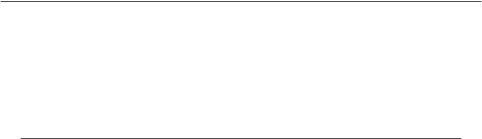

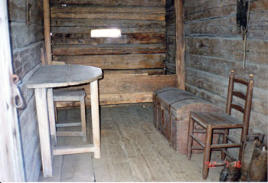

The image to the

right is a farm-

hand's quarter

(drängkammare) at

Kvekgården farm

near Enköping town

(C). Kvekgården is a

today an

homestead museum. Photo Hans Högman, 1992.

During the 18th and 19th centuries there were

more pigor (maids) than farm laborers on farms.

Bohuslän and Skåne, where fishing and heavy farm

work required more male laborers, were

exceptions.

Piga

Pigor (pl.) were servant girls or maids working on

farms. They were usually hired annually to perform

many different tasks. At larger estates or manors

they had more specialized duties such as kitchen

maid (kökspiga), cowshed maid (ladugårdspiga), etc.

Legostadgor

Between 1664 and 1926 the legal relationship

between a farmer and his employees was regulated

in a number of different lawful acts, the so-called

legostadgor (pl.).

Up until 1920, these acts allowed the farmers to

use corporal punishment. After 1858 the farmer

could only use this type of punishment on male

employees younger than 18 and female employees

under 16 years of age.

Wages and working hours were also regulated by

these legostadgor. Besides food, lodging and

clothing, employees also received a small amount

in cash.

The first legostadga (statute) was issued in1664 and

was followed by new statutes in 1686, 1723, 1739,

1805 and 1833. The last one wasn’t abandoned

until 1926.

The slankvecka or frivecka were terms for the free

week when the agricultural laborers could take new

positions at other farms, all according to the

legostadga. The dräng or piga had to report to the

new employer within 7 days from the day (flyttdag)

they left their previous employer.

The “flyttdag” was the day when a legohjon (maid

and farmhand) contract came to an end, normally

after 12 months. Outside of Stockholm, this day

was usually October 24. In Stockholm the flyttdag

was also April 24 (according to the 1833

legostadga). Before that time employees were hired

on September 29 for a period of 12 months.

However, this date was changed because it was

during the busy period on a farm. When laborers

changed employers they were entitled to a free

week, the so-called frivecka (free week) or

slankvecka (slender week).

Husaga - Corporal Punishment

The farmer (master) also had the right to use

corporal punishment (husaga) on his wife and

children. According to the medieval provincial laws

(medeltida landskapslagarna), the master had the

right to moderately use corporal punishment. In

the laws of 1734 there are no references to the

husband’s right to use corporal punishment on his

wife; however it contains the right for parents to

physically punish their children.

The master’s and matron’s right to use corporal

punishment on their employees was regulated in

the different legostadgorna (laws of employment).

The right to use corporal punishment was

completely abolished in 1920.

Landbo

A landbo was a farmer that didn’t own his

farmland, i.e. a farmer that was farming land

owned by someone else (leasehold land). In other

words, a landbo was a type of tenant farmer.

The land he was farming could belong to the

church, the nobility, the Crown or other farmers.

Depending on the type of landownership, this type

of farmer was called kyrkolandbo (a landbo on

church land), frälselandobo (a landbo on noble

land), kronolandbo (a landbo on Crown land) or

bondelandbo (a landbo on a farmer’s land).

The legal relationship between the landbo and the

landowner was regulated by a contract (lease)

called landbolega and in order to be able to farm

someone else’s land a landbo needed to obtain this

lease (landbolega).

The landbo had to pay an annual fee/rent (called

avrad) for the lease.

When a new landbo took over the lease or when

the landbolega (lease) was due for renewal the

landbo had to pay an extra fee.

The landbolega was replaced in the 19th century by

the free tenancy lease. The system with landbolega

was abolished in 1907.

The system of landbo dates back to the Middle

Ages.

The corresponding term for landbo was called

fästebonde in Denmark and leiglending in Norway

and Iceland.

Åborätt

Åborätt (Åbo Right) was an inheritable right of

tenancy for lanbo tenants on Crown land. This

right was introduced at the end of the 18th century.

The Åborätt made it possible for a landbo and his

heir/heiress to stay put on their farms as long as

they paid the tenancy. This right was adjusted by

new regulations in 1808 and 1863 and is still in

force today.

This right of possession of the tenancy gave birth to

the expression Åbo. An Åbo is a tenant farmer who is

farming a leasehold land with an inheritable right of

possession.

There is also another more wide definition of an

åbo and that is a small-scale farmer farming his

own land.

Backstugesittare

Backstugesittare was a term used for people living

in small houses or sheds etc on a landowner’s land

or on the village common land. These poor houses,

backstugorna (pl.), were exempted from taxation.

Backstugesittare were without any assets and were a

motley crowd of people consisting of craftsmen,

farm workers as well as old people and the very

poor.

In the south and southwest parts of Sweden they

were called gatehusmän (their houses were called

gatehus) and in the southern parts of Norrland

utanvidsfolk. On the westcoast they were also called

strandsittare.

The backstuge houses were often collected in

groups of houses outside the cultivated land area

of a landowner’s land (with the permission of the

landowner). Normally there were a small strip of

land belonging to these houses where they could

grow potatoes and keep some pigs and poultry.

Sometimes they also had the possibility to use the

farmer’s farmland. However, normally they earned

their living as farmhands, craftsmen etc. They had

no permanent employments and the

backstugesittarna were often underemployed and

underfed. The number of backstugesittare increased

a lot between 1750 and 1850.

It was common that the backstuge houses only had

three proper walls, so-called dugouts. The fourth

wall was made of earth if the house was built in a

slope.

In other words, the backstuge houses were more

or less hovels/shanties.

Undantag

Most Swedes know about the expression ”att sitta

på undantag” – to be on benefits, however not

everyone knows what this means. This was a term

used in the old agricultural society.

“Undantag” was a kind of pension benefit for the

old couple on a farm. It was common that the old

farmer signed over the farm to for example a son,

prematurely, i.e. the son took over the farm while

the parents were still alive. The law of property

regulated Undantag.

Undantag meant that the old couple was provided

with free lodging, normally in a smaller

house/cottage on the farm for the rest of their life

(undantagsstuga). Further they got the right to a

certain amount of firewood, seed for sowing etc

annually (födoråd).

Undantag could also be negotiated when the farmer

sold the farm. Normally the old farmer then

obtained right to free lodging on the farm,

firewood, milk etc. He could also obtain a certain

right to the yield of the farm in the negotiating

(avkomsträtt).

See also Undantag above.

Inhysehjon

Inhysehjon was a term used for the agricultural

workers who didn’t own any land and were

regarded as a lower class in the countryside. An

inhysehjon was a lodger at a farm and normally

wasn’t closer related with the family on the farm.

Neither were they part of the employees on the

farm. Socially they had a lower standing than the

backstugesittare mentioned above. About 20% of

the agricultural population was inhysehjon in 1855.

To take on an inhysehjon was a way of social welfare

back then. The inhyshjon were people that couldn’t

support themselves.

An inhysehjon could be orphans, disabled, infirm

elderly, the very poor etc.

See also Inhysehjon above.

Fattighjon / Fattighus - Paupers /

Poorhouse

The fattighus (poorhouse) was a building where

the poor and the infirm had a shelter/lodging.

These people were called fattighjon (paupers).

In the 1686 church act it was recommended that

the parishes should build poorhouses. According to

the law of 1734 the parishes had to build them but

that didn’t happen everywhere. Inmates at a

poorhouse were called fattighjon

(pauper/workhouse inmate).

From 1860 and forward there were also a kind of

poorhouses where people of small means, but still

being able to do agricultural work, lived.

Statare

Statare were agricultural laborers receiving

allowance (payment) in kind. They were

employed for 12 months at a time at larger estates.

Normally they were married because the wives

also were expected to work at the estate, milking

cows for example. The word statare indicates that

they were paid in kind (stat). Normally statare only

existed on large estates even if they also could exist

on a few larger farms. Statare were without

property, didn’t own any land or farm animals. In

other words, they were poor agricultural workers

hired for 12 months at a time and lived in the areas

where the large estates were located, primarily the

southern half of Sweden in the flat country areas.

The estates had special kind of barracks for the

statare called statarlängor. They were often in a

poor condition damp, cold and draughty and with

bugs and cockroaches.

The hiring was done during the last week of

October every year. During this week you could see

horse and wagons with statare moving from one

estate to another – it was always greener grass on

the other side – they hoped for a better life at

another estate. It was often the miserable lodging

conditions that made the statare to take position as

a statare at another estate.

There were different kinds of statare depending of

what kind a laborer work they did.

They system of statare began in the middle of the

18th century and wasn’t abolished until 1945. The

number of statare families reached a peak in the

beginning of the 1900’s.

The system of statare did not exist in the other

Scandinavia countries. However, there was a similar

system in the Baltic countries as well as in

Germany.

It did not exist in the English spoken world, which

means it is difficult to find an English expression for

statare.

More information of the system of statare.

Related Links

•

Croft and Crofters (Torp and Torpare)

•

Landownership

•

Agricultural Yields and Years of Famine

•

The Conception of Socken (Parish)

Source Reference

1.

Swedish National Encyclopaedia, NE

2.

Wikipedia

Top of page

The Old Agricultural

Society and its People