Copyright © Hans Högman 2022-04-02

Gamla jakt- och

fångstmetoder (3)

English

History of Old Hunting and

Trapping Methods - Sweden

Introduction

Hunting involves searching for, tracking, pursuing,

capturing, and killing game. Originally, hunting was

used to obtain food, clothing, and footwear. The

hunting methods used varied greatly depending on

the terrain, prey, and technological factors.

The title picture above shows "Wolf hunting in

Westergötland" by Fritz von Dardel in 1847. A sled

with three men and a pig is pursued by two wolves.

Image: Wikipedia.

Fishing is the catching of animals in the water, such as

fish, shellfish, etc., either professionally or as

recreational fishing (i.e. either subsistence fishing with

professional gear or sport fishing). A person who

engages in fishing on a professional basis is called a

fisherman.

Related Links

•

Old hunting and trapping methods, page 1

•

Old hunting and trapping methods, page 2

•

The Old Agricultural Society and its People

•

The conceptions of croft (torp) and crofters

(torpare)

•

The Concept of Nobility

•

Summer Pasture - Fäbodar

•

The subdivisions of Sweden into Lands, Provinces

and Counties

•

Map, Swedish provinces

•

Map, Swedish counties

Source References

•

Det gamla Ytterlännäs, Sten Berglund, 1974.

Published by Ytterlännäs Hembygdsförening.

Chapter 41 (page 395).

•

Jaktens historia i Sverige : vilt - människa -

samhälle - kultur, Kjell Danell; Roger Bergström;

Leif Mattsson; Sverker Sörlin. 2016.

•

Vilt i Sverige och Europa – igår, idag och imorgon,

Daniel Ligné, Svenska Jägarförbundet

•

Is the fear of Wolves justified? A Fennoscandian

perspective, 2002. John D.C. Linnell, Erling J.

Solberg, Scott Brainerd, Olof Liberg, Håkan Sand,

Petter Wabakken, Ilpo Kojola.

•

Makten över jakten, article in Populär Historia by

Gunnar Brusewitz 2001.

•

Om fiskfångst med snara. Edvard Wibeck. 1915.

•

Fisket i stockholms skärgård under historisk tid.

Havsmiljöinstitutets rapport nr 2021:3. Henrik

Svedäng och Carl Rolff.

•

Björn i Nordisk familjebok (andra upplagan, 1905)

•

Nordisk familjebok / Uggleupplagan. 12.

Hyperemi - Johan / 1203-1204

•

Wikipedia

•

Swedish church books

Top of page

Fishing Rights in former Days

Already in the Middle Ages, fishing on the coast and in

the rivers was considered to belong to the Crown or

the King, water regalia. In the 16th century, King Gustav

Vasa extended the Crown's right to include lake

fishing, the tax revenue from which went to the Crown.

In other words, it was not only the productive salmon

fishing in the rivers that were taxed but also the

fishing in the lakes. Preserved tax documents from the

time of Gustav Vasa and his sons bear witness to this.

Baltic Herring Fishing along the Coast of

Norrland - The Gävle fishermen

Gustav Vasa thus strengthened the Crown's legal claim

- called the King's rightful commons - and extended

the tax obligation also to the Baltic herring fishing in

Norrland, which had previously not been a taxable

commons and available to all and sundry. In 1557,

Gustav Vasa granted a royal privilege to fishing citizens

from the City of Gävle, who now had the exclusive

right to Baltic herring fishing along the coast of

Norrland in return for paying every tenth barrel of

fish to the Crown. Gävle was then the only city (with

town rights) in Norrland.

This exclusive right was loosened up somewhat by

subsequent rulers in the latter part of the 16th and

17th centuries, so that fishing citizens from towns on

Lake Mälaren, such as Enköping, Torshälla, Strängnäs,

and Västerås, were also allowed to fish along the coast

of northern Sweden. But in time these more southerly

fishermen abandoned the area and the Gävle citizens

were left alone.

Gävle fishermen established fishing villages (Swe:

fiskelägen) from Gävle all the way up to northern

Ångermanland. These fishing villages came to be

known as Gävle fishermen’s ports. When new towns

were founded along the Norrland coast, the situation

became more complicated. After Hudiksvall and

Härnösand were granted city rights in the 1580s, their

burghers tried to take over Gävle's fishing villages.

After two more towns were added in the 1620s,

Söderhamn, and Sundsvall, the burghers there also

tried to take over nearby fishing grounds.

On Brämö Island south of Sundsvall in Njurunda

parish, there are two communities, Sanna on the

mainland side of the island where the pilot station was

located, and Norrhamn on the northern side of the

island. Norrhamn consists of the old fishing villages

Hamn and Viken. Norrhamn became a fishing village

for the Gävle fishermen. In Norrhamn is the Brämö

chapel from the early 17th century, and to the east is

the Brämö lighthouse, which was built in 1859. The

oldest of the current fishing cottages date from the

early 18th century.

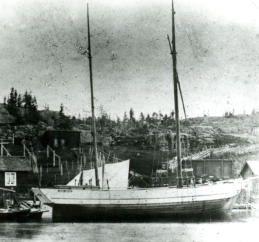

The image shows the fishing village Norrhamn on

Brämö Island, Njurunda parish, south of Sundsvall,

around 1910 - 1914. Image: Sundsvall museum, ID:

SuM-foto019118.

In 1623, the citizens of Sundsvall wrote to the

Councillor of the Realm Johan Skytte, stating that the

new town needed additional privileges, especially

fishing grounds, to develop. The town was then

allowed to take over the Gävle fishermen’s old fishing

grounds of Lörudden and Brämön in Njurunda parish

and Rödviken in Tynderö parish. The Gävle fishermen

remained, but from then on as tenants.

As Sundsvall grew, however, the demand for fishing

grounds from the citizens increased, and in 1701 the

city simply decided to turn the Gävle inhabitants away.

As a result, some of the Gävle fishermen became

residents of the area. Soon the old long-distance

fishing in Medelpad province was a thing of the past,

while several fishing villages were established around

the city of Gävle.

In Härnösand in 1652, the mayors decreed that "no

stranger" would henceforth be allowed to fish closer

than 20 km from the town. This meant that the Gävle

fishermen had to leave Storön and Hemsön. In 1707,

the Gävle fishermen agreed with the citizens of

Härnösand that they would jointly use the fishing

grounds, except those located less than 20 km from

the town.

In 1766, the Crown's water regalia was abolished by

a new fishing charter, which meant that anyone who

owned a coastal strip also had the right to fish. This led

to the final abolition of the Gävle fishing privileges in

1773. The burghers of Härnösand and Sundsvall

bought the fishing rights.

From around 1740, the Gävle fishermen were

organized in a so-called society (guild), known as the

“fiskarsocieteten”, i.e. the fishermen's society.

The town fishermen of Gävle sailed north in May. At

the beginning of the 18th century, they mainly used

covered yachts and uncovered or half-covered ketches

known as “haxar” (haxe in the singular), but also a

type of boat that was known as “skötbåtar”.

In the middle of the 18th century, the members of the

Gävle Fishermen's Society (guild) had about 60 “haxar”.

These freighters were used to transport the families of

the town fishermen to the fishing grounds, where sons

and farmhands were left to do the fishing. The father

of the house himself would then leave the port to sail

along the coast to do freight service, sometimes as far

as Pomerania or Danzig. In September or October, the

family would be picked up again. The ships carried all

kinds of small pets such as chickens, goats, pigs, and

ducks, as well as the food needed for the stay at the

fishing grounds. Throughout the summer, fish was

preserved in the form of salted Baltic herring,

fermented Baltic herring (Swe: surströmming), and

“krampsill” (sun-dried herring). In the autumn, this was

transported back to Gävle for sale. In 1742, 6,500

barrels of salted herring were taken home, and in

1816 no less than 10,000 barrels.

A "haxe" is a small, flat-bottomed coastal working

vessel (ketch), rigged as a galleass, used in the 18th

and 19th centuries. The name “haxe” comes from

“haaksi” in Finnish, an archaic word for a small cargo

boat, or small vessel (ketch). The haxe was used mainly

for shipping, but also

for fishing, along the

Norrland coast.

The image to the right

shows the ketch (haxe)

“Anna” moored at a

fishing village in Höga

kusten, Ångermanland.

It was owned by the

fisherman Erik August

Grellson. The boat was

built in 1817 in Gävle. Image: Sjöhistoriska museet, ID:

Fo24936AB.

The Nordic “skötbåt” boat is essentially a gig boat built

in the past from wood, mainly used for fishing with

“skötar” for Baltic herring. The boat was usually an

open and wide boat with one or two pairs of oars and

a spritsail. “Skötar” are nets used on the Baltic coast

for herring fishing. The

length of these boats was

just over 7 m.

The image to the left shows

a sketch of a Finnish

“skötbåt”. Image: SLS,

Folkkultursarkivet, signum:

sls410b_1.

More information on fishing and fishing methods

Gistvall - Net-Drying Racks

At the fishing villages, each fisherman had net-drying

racks known as “gistvall”, with fixed wooden racks, on

which the nets could be hung up to dry. A “gistvall” is

an open flat area of ground provided with a rack for

hanging fishing nets to their full extent for drying, to

make it easier to clear the nets of seaweed and to

check for damage that may need repairing. The “gist”

was a standard piece of equipment on the shore

adjacent to the jetties where fishing nets were taken

ashore after fishing was completed and was usually

erected on a flat larger grassy area so that the nets

could not catch on anything on the ground. To “gista”

nets means to hang and dry the nets. In the picture of

the ketch Anna above, you can see a “gistvall” on land

behind the boat. “Vall” means grassland.

Who fished

On the Baltic coast, fishing was largely a sideline to

farming but also to various urban industries (urban

citizens). Fishermen used to be divided into the

categories of "professional fishermen" and "sideline

fishermen". The latter group is made up of those who

regularly fish for sale but whose main income is

derived from other occupations and of those who are

purely subsistence fishermen. However, there is no

clear dividing line between pure professional

fishermen and typical sideline fishermen.

A large number of farmers were regularly engaged in

fishing for sale to a greater or lesser extent, and it may

depend on the circumstances whether their main

source of income is fishing or farming.

More information on fishing and fishing methods