Copyright © Hans Högman 2022-01-02

Road Maintenance Obligation

In King Magnus Eriksson's nationwide National Law

Code and Town Law from the 1350s, there were also

laws for the maintenance of Sweden's roads. Under

the Provincial Act's Agriculture code, farmers were

obliged to maintain the road network. Special

division lists were introduced where each stretch of

road was divided into different road lots, and each

of these road lots was to be maintained by the

landowning peasants along the respective road.

In order to keep track of the boundary between the

different road lots, the farmers set up special road

maintenance stones (Swe: väghållningsstenar) at

each end of the allotted lots. These stones were

often marked with the name or initials of the farmer

and the farm.

It also happened that a farmer could have road lots

in several places in his parish, i.e. the lots did not

have to be next to each other.

The landowning farmers were thus obliged to

maintain the roads, i.e. the mantal-set land, and the

roads had to be maintained twice a year, usually

before the spring sowing and after the autumn

harvest. Road maintenance was checked annually by

special road and bridge inspections.

The Swedish National Land Survey Agency (Swe:

Lantmäteriet) was established in 1628 and the land

surveyors carried out road division assignments.

The medieval National Law Code stipulated that the

road width for highways and district roads should

be 10 Swedish cubits (6 m) and for village roads 6

cubits (3.6 m).

The farmers were thus obliged to keep the road

passable over their own land. However, those who

did not have a road across their land did not escape

participating in the road maintenance effort.

Farmers' Road Maintenance Obligation Ends

For centuries, the farmers had complained about

the obligation to maintain roads, and the Peasantry

at the Diet of the Four Estates complained about

this. The burden was gradually distributed so that it

also came to rest on divided off agricultural

property, but also on other taxable property. A new

organization of the road system was created and

came into force in 1895 with so-called road

municipalities, which were also based on municipal

autonomy. The new road municipalities, divided into

different road districts, usually covered an entire

court district.

The road municipalities were a kind of municipality

with its own levying right, an administrative road

board (Swe: vägstyrelse), and a decision-making road

council (vägstämma). Every taxpayer had access to

the road council meeting and the right to vote. Like

municipal voting rights, this was graduated, i.e.

voting was based on income and property value

based on "fyrktal". Agricultural properties were still

obliged to carry out road maintenance but had a

lower estimated road tax per fyrk. The roads within

the road district were divided into sections according

to the assessed value of the farm, and the sections

were marked with road signs following the roads. An

innovation was that the Government provided a

subsidy for road maintenance of 10% of the

estimated cost.

A change in the law in 1921 gave the road

maintenance districts the right to carry out all in-

kind road maintenance through the road board. The

medieval burden placed solely on the land was thus

finally removed.

Northern Trail (Norrstigen)

Along the Norrland coast, there was a well-known

route, Norrstigen (The Northern Trail). It was to be

cleared to a width of 6 cubits (3.6 m). In the Middle

Ages, there was hardly any roadway to speak of, as

wheel carts were not used. But roads had to be

provided to the parishes inland for their connection

to the trail. These roads (paths) were of a lower

standard than the Norrstigen.

For the farmers who maintained the roads, it was of

course a heavy burden to build and maintain these

roads. But both judges and local police officers

checked that the roads were passable and

prosecuted any negligent road-keepers.

Norrstigen later came to be known as

Kustlandsvägen (The Coast Highway). During the

20th century, the Stockholm-Haparanda section was

renamed Riksväg 13 (National Road 13). Nowadays

this stretch is part of the E4 (European Road 4).

Ådalsvägen (Ådalen Route) was a detour from the

Northern Trail, which followed the Ångerman River

from its estuary up towards Sollefteå town.

1500s

In 1559, King Gustav Vasa decreed which roads

between the counties should be the main roads and

they should be widened to roads that could be used

by horses and wagons. The old riding paths should

be cleared, widened, straightened and the road

surface leveled. However, the work was slow, the

roads continued to be stony and rough. But it was at

this time that roads began to be built in contrast to

the old natural paths. Stone-filled caissons were

used for longer wooden bridges over watercourses.

Roads were now generally laid at the boundaries

between estates and often in the area between

woods and fields, winding around fields and

meadows across the landscape.

1600s

During the days of Sweden’s Great Power Era, there

was a considerable increase in the demand for

passable roads, roads that could also serve as

marching routes for the army with its heavy horse

and carriage transport.

In 1628, the newly established National Land Survey

Agency began to measure and map the roads. These

maps were considered military secrets at the time.

Under the Constitution of 1634, Sweden was

divided into counties, with a County

Administrative Board (Swe: Länstyrelse) in each

county. With the creation of the County

Administrative Boards, road management was

improved. However, road work was primitive and

was done by hand with shovels, pickaxes,

wheelbarrows, horses, etc. Bridges were usually built

of wood, but pontoon bridges also existed.

Queen Kristina's Innkeepers' Ordinance of 1649

included rules for inns to be established every 20 km

(12 mi) and milestones to be erected along the

roads at every 10 km (6 mi). The roads were to be

measured so that all 10 km stretches were of equal

length. The county governors were given the task of

ensuring that the road maintenance obligation was

fulfilled. The governors were also responsible for the

erection of milestones.

At county and parish borders, there were sometimes

so-called rightly stones (Swe: rättestenar) urging

travelers to behave lawfully.

Road policy in the 17th century was mainly to

improve the standard of the existing roads; the

simple hoof paths were to be improved to become

cart paths and the cart paths were to be

transformed into almost stone and hill free carriage

roads.

1700s

The 18th century was a time of road building. Many

works were established in the 18th century and the

need for roads for transport increased dramatically,

and in all months of the year. Demands on roads

increased and existing roads were improved and

new ones were built. The demand for faster travel,

better carts that could carry larger loads, etc.,

contributed in the following century to a lot of work

being done to remove the worst uphills and, above

all, to improve the road surface.

In 1718 Sweden receives a decree on right-hand

traffic, but under the 1734 Law, left-hand traffic

was introduced. It also included an ordinance on

signposting to communities and clarifications on

road maintenance.

In the 1734 Act, the Agriculture Code (Swe:

Byggningabalken) provides, among other things, for

the division of roads into public roads, church

roads, mill roads, and village roads. A chapter

deals with road maintenance and the conditions for

building roads, as well as the obligation to clear and

maintain roads and bridges and “road shall be laid in

the County where it is needed”. There is also text on

milestones and signposting. Concerning winter road

maintenance, there is only mention of winter roads

on ice, but nothing about snow clearance.

The medieval National Law Code stipulated that the

road width for highways and court roads should be

10 Swedish cubits (6 m) and for village roads 6 cubits

(3.6 m). As for road width in the 18th century, these

measurements are repeated in the Agriculture Code

in the 1734 Act. This law was in force until the 1891

Road Act, which stipulated a road width of 6 m for

highways and 3.6 m for village roads.

{A Swedish cubic (aln) = 59 cm}

It was not until the middle of the 18th century that

the major highways could be said to be in such good

condition that, with some difficulty, it was possible to

travel on them by horse and carriage. In 1752 it was

decided that stone bridges should be built on public

roads, so-called arch bridges. Although the roads

were still poor, Sweden, with its solid bedrock, still

had relatively good roads internationally.

However, the bulk of long and heavy haulage has

traditionally taken place mainly in winter with snow

conditions and especially on winter roads over the

ice.

1800s

The introduction of a central government agency

for the road system was brought up by Captain Axel

Erik von Sydow in a small publication "The benefits

and necessities of public work" in 1840. The proposal

aroused great interest among King Karl XIV Johan

and was the subject of a royal decree on August 6.

In 1841, the "Royal Board for Public Road and Water

Construction" was established, i.e. what later became

the National Road Administration (Swe: Vägverket).

The name "Royal Board for Public Road and Water

Construction" changed in 1882 to the Royal Road and

Water Construction Board (Kungl. väg- och

vattenbyggnadsstyrelsen).

Initially, and well into the 20th century, the Agency's

responsibility was only to allocate government

grants for the construction of roads, bridges, and

canals, and to check that the work had been carried

out properly. It was still the responsibility of the

farmers to carry out the actual construction of

the roads and to maintain them.

In the 19th century, the roads face competition from

both steamship traffic and the railways in terms of

travel. In 1832, the Göta Canal was completed,

enabling both passenger and freight travel across

Sweden. To improve and to make the roads more

passable, macadam (crushed gravel) is laid on the

road surface to make it more durable and less

muddy.

With the expansion of the railroad in the second

half of the 19th century, roads were also built to the

new station communities growing around the

railway stations.

In 1891, Parliament passed a new Road Act, which

came into force in 1895. Under the new Act, road

maintenance obligations were distributed according

to the assessed values of all rural properties. The

landowning farmers were no longer solely

responsible for maintaining the roads. Each

landowner who was obliged to maintain a road was

given a certain number of road lots to maintain in

proportion to the size of the property. At the end of

the 19th century, there were about 360.000 road lots

in the country.

Sweden was divided into 368 road maintenance

districts, which were usually made up of the

respective parish, county district, or court district.

The 1891 Road Act established the old road width of

6 m for highways and 3.6 m for village roads.

The image shows travelers with a horse and cart in

Småland province, Sweden. Drawing by Fritz von

Dardel (1817-1901). The image also shows a

milestone and a closed gate across the road.

Road Gates

In the past, there could be gates even on public

roads, gates that had to be opened and closed by

the person passing the gate. In 1857, the County

Administrative Board decided that the gates should

be removed during the seasons when they were not

needed for livestock. In 1864 it was forbidden to put

up a gate across the road without the permission of

the County Administrative Board, this applied to

highways and county district roads. In 1927, a

general ban on gates on public roads was

introduced.

1900s

At the beginning of the 20th century, motoring is on

the increase with more traffic on the roads. This

meant that the old medieval road management

could no longer meet the new demands on roads.

Instead, a road tax (Swe: vägskatt) was introduced

and road maintenance was taken over by road

funds (Swe: vägkassor), one for each road

maintenance district. The road funds received

financial resources in the form of road taxes and

government grants. The road boards (vägstyrelser),

which managed the road funds, employed road

engineers and road workers.

In 1922, Parliament decided to introduce an

automobile tax. The tax, which initially went directly

to road maintenance, was distributed to both urban

and rural areas by the Royal Road and Water

Construction Board (Swe: Kungl. väg- och

vattenbyggnadsstyrelsen). From 1924, the County

Administrative Boards could also employ road

consultants.

In the 1934 Road Act, roads are divided into

highways and rural roads. No provision is made for

road widths.

In 1937, the old natural road maintenance system

was completely abolished and the former 368 road

maintenance districts were merged into 170 road

districts. Road maintenance could now be carried

out more efficiently, including with the help of

machinery, but road maintenance was still a

municipal affair.

On 1 January 1944, roads and road maintenance in

rural areas were nationalized. The agency

responsible for central administration became the

Royal Road and Water Construction Board. Road

administrations were now established in each

county.

During the high unemployment of the 1920s and

1930s, many new roads were built in an effort to

keep unemployment down. It was the Government

Unemployment Commission (Swe: Statens

Arbetslöshetskommission, AK) that organized this

construction.

The image to the

right shows a

road

construction

between

Alingsås-

Vårgårda in 1933

with so-called

AK workers.

Photo: Alingsås

museum, ID:

AMB 15908.

Road Surfacing

According to the old provincial laws, roads and

bridges had to be inspected every year. It was

customary to gravel the road just before the

inspection. Graveling was prescribed in 1734 when

the road keepers were given access to gravel pits.

The natural gravel then used as road surface

material was later out-competed by crushed gravel.

In 1953 it ceased to be used altogether.

In 1854, macadam was laid on the road between

Malmö and Lund, after which this water-bound

macadam surfacing came into use in Sweden.

The first Swedish asphalting of a road was done in

1876 on the street "Stora Nygatan" in Stockholm.

The first asphalting of a highway in Sweden was

probably carried out in the Stockholm area in 1909,

using macadam and a bituminous binder. The length

of road paved increased rapidly until the outbreak of

World War II when there was a shortage of

bituminous binder. In the late 1950s, roads also

began to be paved with oil gravel.

In 1906-1907, concrete paving was laid on some

streets in Malmö, southern Sweden. The first

concrete pavement on a highway in Sweden was laid

in 1923 on a 400 m stretch of road between

Stockholm and Södertälje. During the post-war

period, several roads in Sweden were paved with

concrete. The first concrete-surfaced motorway was

opened in 1953 between Malmö and Lund. Concrete

roads are not common in Sweden and today there is

just under 70 km of concrete roads.

Bridges

The term bridge does not only refer to cantilever

structures but in general to any kind of built-up road

or road bank. They were usually built over the banks

of the river at ford sites. Medieval provincial laws

contain information on bridge building and

maintenance.

Wooden Bridges

The simplest wooden bridges were so-called

corduroy roads (Swe: kavelbro), which are a

reinforcement for simple roads over marsh ground.

They consist of logs laid close together across the

direction of the road, like sleepers on a railway. The

logs distribute the load of a vehicle's weight and

prevent it from sinking into the ground, and they

were laid directly on the marshy ground.

The most common type of actual wooden bridge

was some form of beam bridge (Swe: balkbro).

Sometimes high wooden abutments were built, such

as stone-filled timber caissons. Stone-filled timber

caissons were also used in the water for longer

bridges.

A special type of wooden bridge was the pontoon

bridge, (Swe: flottbro), which was especially common

in the Dalälven River. A pontoon bridge is a special

type of bridge where the roadway is supported by

rafts, which float on the water.

Related Links

•

Road History, page-2, Terminology

•

Inns and Stage Services

•

Summer Pasture

•

The Conception of Socken (parish)

•

Domestic Travel Certificates

•

History of the Swedish Police

•

History of Railways in Sweden

•

History of Göta Canal

•

Old Swedish Units of Measurement

•

Agricultural Land Reforms, Sweden

Source References

•

Vägen i kulturlandskapet, vägar och trafik före

bilismen, Vägverket, 2004

•

Det gamla Ytterlännäs, Sten Berglund, 1974.

Utgiven av Ytterlännäs hembygdsförening.

Kapitel 39, sid 368 och framåt.

•

Hur klövjestigen blev landsväg, Gösta Berg, 1935.

(Svenska kulturbilder / Första utgåvan. Andra

bandet (del III & IV), sid 269 och framåt.)

•

Gästgiveri och skjutshåll, Ur det forna reselivets

krönika, av Sven Sjöberg. Ur årsboken Uppland,

1959.

•

Stigen av Lars Levander, 1953

•

Svenska Akademins Ordbok, SAOB (Swedish

Academy Dictionary)

•

Wikipedia

•

Lantmäteriet (The National Land Survey of

Sweden)

Top of page

Swedish Road History (1)

Stone Bridges

The oldest stone bridges were simple stone beam

bridges (Swe: Stenbalkbro) with a very limited span.

They consisted of one or more flat cut stones resting

on stone abutments.

From the end of the 18th century and for most of the

19th century, the most common type of arched

bridge was built of wedged stone in a dry stonewall,

i.e. without mortar. At the end of the 19th century,

mortar began to be used as a binding agent. At that

time, stone arch bridges (Swe: Stenvalvbro) were

usually built of smooth-cut stones and stone arch

bridges were built until the 1930s.

According to a royal decree of 1752, all bridges built

with public funds had to be made of stone.

The image shows a stone arch bridge in Lerum.

Photo: Vänersborg Museum, ID: VMLER0030.

Iron Bridges

The first iron bridge built in Sweden crossed the

Göta Canal and was built in 1813 in Forsvik,

Västergötland. In the beginning, cast iron was used. It

was not until the 1880s that steel road bridges

became common. Until the 1920s, when concrete

rapidly gained ground, this was the predominant

bridge-building material. The most common type of

construction was the beam bridge. However, the

roadway was usually made of wood.

Concrete Bridges

The first concrete bridges built in Sweden were in

1887 at Jordberga and across the Höje River in Lund,

both in Skåne. At the beginning of the 20th century,

concrete bridges became common.

The Skuru bridge in Stockholm was built between

1914 and 1915 and was the first major bridge to be

built in reinforced concrete using modern

construction principles. After this, concrete bridges

began to displace steel bridges even for larger spans.

The image shows

the Haraberg bridge

(concrete bridge)

over the Ljungan

River in Kvissleby,

Njurunda, south of

Sundsvall. Photo: Sundsvall Museum, ID: SuM-

foto013586.

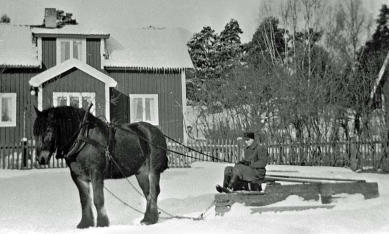

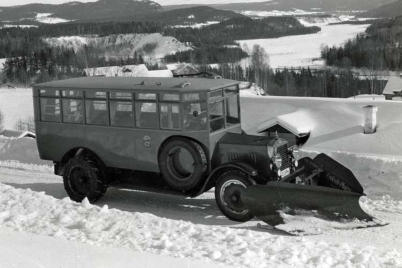

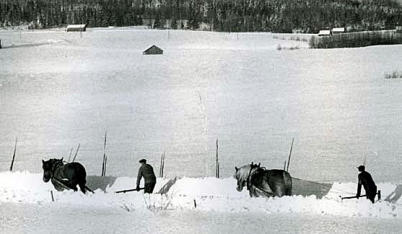

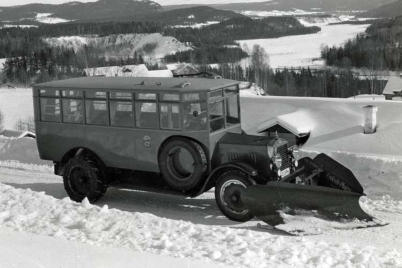

Winter Road Maintenance

In the Middle Ages, there was no regular winter road

maintenance. The snow-covered road surface was

"smoothed down", i.e. the snow was cleared by driving

back and forth with a horse and sled (similar to snow

rolling). In this way, the road became passable. The

first direct mention of winter road maintenance is in

the 1687 county governor's instructions. The governors

were now given the task of ensuring that roads and

bridges were maintained. This did not only apply to

summer roads but also to roads "that are used and

needed in winter".

In winter, farmers took it in turns to keep the private

roads open when snow fell. In order to keep track of

who was next to do the snowplowing, there was a

special system without paper and pen. They had a

kind of rallying stick, a so-called plow block or road

stick, on which the name or other owner’s marks of

those who were to be responsible for plowing were

engraved. The person who had made his

snowplowing turn then handed over the piece of

wood to the next person in line.

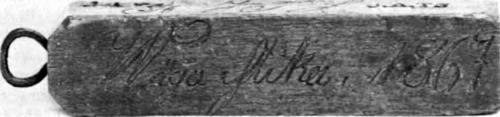

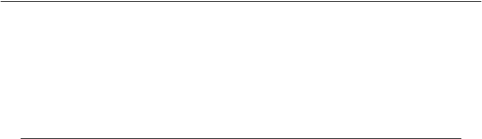

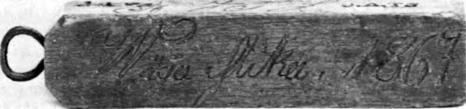

The image shows a plow block (plogklomp) or road

stick (vägsticka) from 1867 in Ytterlännäs,

Ångermanland. Image: Det Gamla Ytterlännäs, page

378.

It was the village councils (Swe: Byalag) that were

responsible for plowing the snow by forming plow

teams (Swe: ploglag) consisting of the landowning

villagers. The public roads within the parish were

divided into lots of different lengths according to the

mantal-set land (Seland in Ångermanland) included in

the plowing team. The entire length of the roads in

the parish was measured, taking into account the

difficulty of plowing different parts of the roads. In

Ytterlännäs parish, Ångermanland, the snow plowing

was regulated in 1866 so that 293.77 feet of the road

were placed on each piece of seland-set land in the

parish. A village or a few homesteads in a village then

formed a plow team whose total number of seland

was multiplied by the above-mentioned figure, which

then became the length of road for which the plow

team was responsible. In total, the whole parish was

divided into 24 plow teams, and at the boundary

between the different plow teams' stretches, a visible

mark was put up.

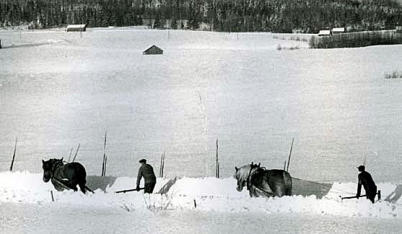

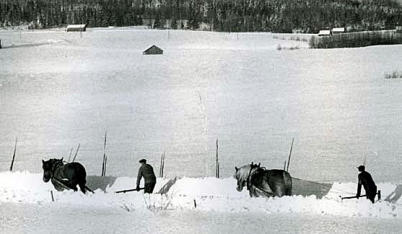

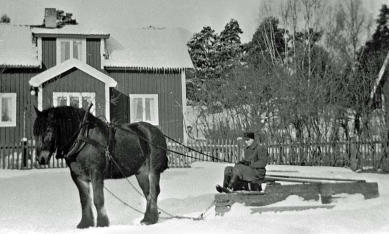

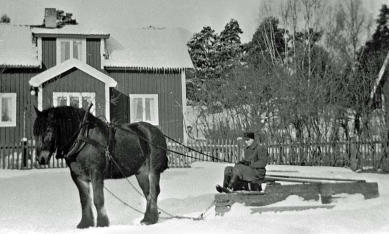

The horse-drawn snowplow is invented in 1730,

shortly followed by the road scraper (grader). In open

landscapes, avenue trees are planted to mark the

road in winter and provide cooling shade in summer.

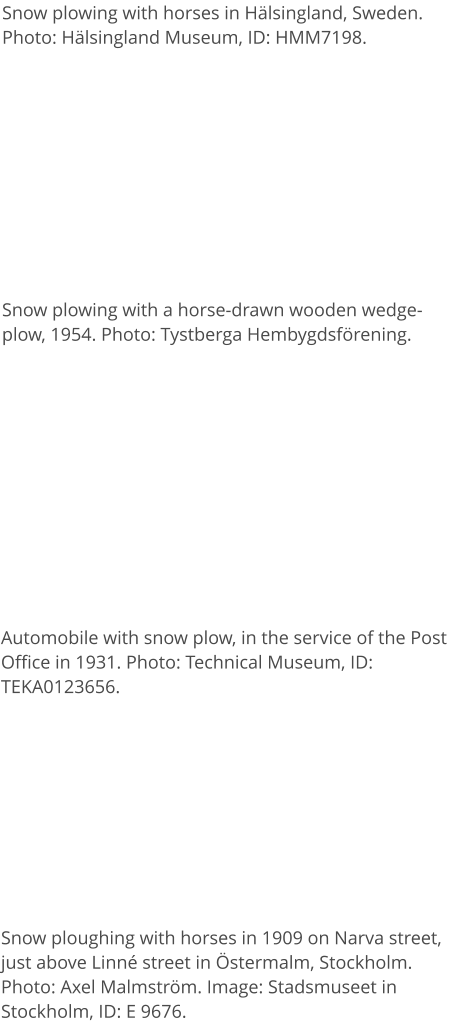

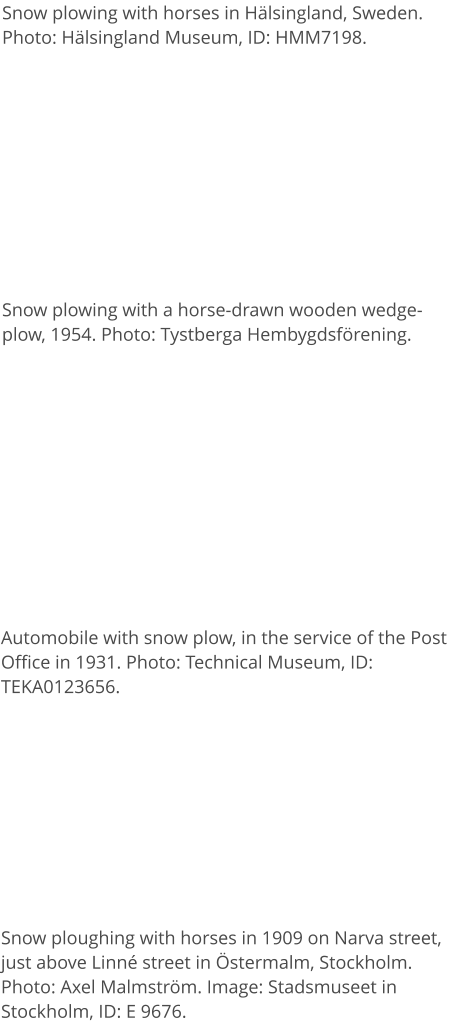

At the beginning of the 20th century, the so-called

half-plow was introduced. It was easier to handle

and required less traction than the standard wedge-

plow. The half-plow consisted of only one plowing

side, which meant that one half of the road was

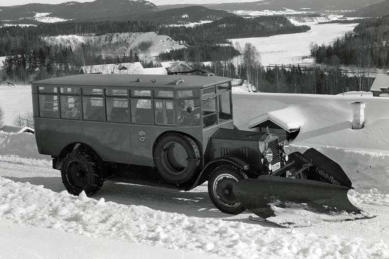

plowed at a time. In Lycksele, modern machine

plowing was introduced in 1925. Here the first

Swedish car plow was demonstrated, a front-end

plow called the Lycksele plow.

In Sweden, anti-slipperiness measures in the form

of road sanding (gritting) on highways were first

introduced with car traffic in the 1920s. Gritting was

a difficult balancing act between the different needs

of car and sled traffic. In 1949, the first tests of anti-

slip road salting were carried out in Västmanland.

Introduction

Long ago, roads were not the first choice for travel,

either for long journeys or for journeys with heavy

goods. Waterways were more important, such as the

sea, lakes, and rivers, which were traveled by boat. In

winter, when there was snow and frost on the

ground and the lakes were frozen, the easiest way to

get around was by horse and sled, which allowed the

shortest route to be taken over both land and water.

On land, there was only a need for paths that could

be followed on foot or horseback. At that time, it was

enough to simply clear away obstructing bushes and

branches in the forest. Paths were avoided on the

sunken ground, where temporary obstacles could be

found. Rather, paths were built on hills and dry

ridges.

Where farms or villages were located on

watercourses, it was often easier to get around by

sea.

But as communities grew, there was a need for

better connections between them. The Hälsinge

Provincial Act from around 1320 already mentions

roads, dividing them into public roads and private

roads. The former included the road to the district

court and the church. So, according to the law, there

should be a road to the church, for example. The

obligation to build and maintain public roads and

bridges lay with the landowners, i.e. the resident

peasants. This obligation was later distributed

according to each farmer's landholding, i.e. the

mantal-set land.

It was a fine for neglected road maintenance. In

winter, when the ice had settled, roads on land were

abandoned in many places, and travel took place on

the ice over lakes or by sea. These winter routes were

also regulated by law.

Natural road staking is the oldest variant where the

road follows the natural topography and vegetation.

Often these are old narrow paths that have been

widened and reinforced over the years to form the

road that exists today. These roads are often crooked

in both plan and profile.

In the second half of the 19th century, there were still

many rural villages that lacked access by horse and

cart in the summer. In Ytterlännäs parish in southern

Ångermanland, the villages of Majaån, Västertorp,

and Västansjö had only their footpaths and hoof-

paths to reach the main road to Forsed, where they

had their summer vehicles for the journey down to

the village. It was not until the 1890s that they had a

passable road to the villages. The single farm

Abborrsjön, further to the east, was roadless until

1936.

Paths and Roads

Footpath

A footpath (Swe: gångstig) or path is a narrow route

primarily for pedestrians. Natural paths are

common, especially in wooded areas and other

areas with "natural" ground vegetation. The natural

path has been created by the wear and tear of feet

and perhaps once hooves, which has eroded, worn

down, and removed ground vegetation along a

narrow strip. The presence of the path has then led

to further walkers choosing the same route, thus

preventing it from growing again. The benefits of

choosing an existing path in the woodland are better

access and better wayfinding.

Hoof Path

Transport by a pack-animal (Swe: klövja) means

placing a load on a pack animal, i.e. transporting a

load on the back of a pack animal. The pack

animal might be a horse, donkey, ox, reindeer, etc.

Often special packsaddles or pack bags are used

which hang on both sides of the animal to distribute

the weight evenly. Transport by a pack animal is

particularly used in rough terrain, where wheeled

transport is impossible. A hoof path or hoof trail

(Swe: klövjestig) is a path/road on which goods can

only be transported loaded on hoofed animals, i.e. a

path which is slightly wider than a footpath.

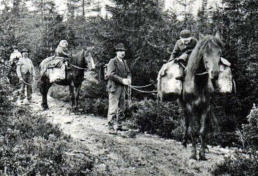

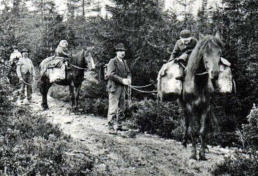

The image shows a

hoofed trail with pack

animals and

packsaddle. Hoof trail

to summer pastures in

Leksand parish,

Dalarna. Photo: From

“How the hoof path

became a road”.

Riding Path/Trail

A trail or path (Swe: ridstig) accessible only to

equestrians; as opposed to a footpath or trafficable

road.

Cart Road

A cart road (Swe: kärrväg) is a type of small road,

often in the woods, used for driving a horse and

cart (single-axle) and other simple wheeled vehicles.

Unlike a hoof path, a cart track could be used for

horse-drawn carts on bare ground, for example by

farmers bringing hay home from their fields. The cart

track is characterized by two-wheel tracks and a

trampled path following the horse's hooves in the

middle of the road. Where there was no cart track,

winter road transport was often the only option for

transporting large quantities of goods.

Wagon Road

Wagon road (Swe: vagnväg); a (constructed) road

with two-wheel tracks that could be traveled by

horse and wagon; also in more special use, if road

for (horse-drawn) wagon transport.

A wagon road is a major cart road capable of running

with a horse and carriage, i.e. two-axle vehicles.

Wagons with wheels allow much higher weight than

carrying the load (of a person or an animal), but only

if there is a road, otherwise a wagon is of no

advantage. A wagon has a superstructure or basket

that rests on two axles (sometimes one axle) and

usually four wheels and can be driven on a wagon

road or highway.

Sunken Lane (Hollow Way)

A sunken lane or hollow way (Swe: hålväg) is a relic

of the past consisting of a furrow in the ground

where an ancient road passed. The furrow has been

formed by the wear and tear of hooves and feet, and

by running surface water.

In slopes and where different paths could converge

towards a ford, there was particularly high wear of

feet and hooves in combination with water erosion.

There, quite deep tracks could gradually dig into the

ground. This type of "road" is called a sunken lane.

Many of these have been preserved. The largest

system of sunken lanes in Sweden is found near

Sandhem Church in Västergötland, where in places

there are over 20

parallel "lanes" of

hollow roads.

The image shows a

hollow way in the

nature reserve

Slereboån Valley near

the village of Röserna

in Risveden,

Västergötland. Photo: Wikipedia.

Highway

A highway (Swe: landsväg) is a major (constructed)

public road overland; a main road, linking two or

more major towns.

“Land” in the Swedish term “landsväg” emphasizes

that it is a road overland as opposed to a waterway.

Village Road

A village road (Swe: byväg) is a road leading from a

public road (usually a highway) to and through one

or more villages or individual farms, i.e. a maintained

minor road.

Church Road

A church road (Swe: kyrkväg) is a local road leading

to a church.

Courthouse Road

A courthouse road (Swe: tingsväg) is a local road

leading to a district courthouse.

National Roads

National road or national highway (Swe: Riksväg)

is a classification of roads that exists in several

countries. The meaning of the classification varies

from country to country, but national roads are often

roads that are considered important for the

country's infrastructure. In Sweden, roads with

road numbers from 1 to 99 are called Riksvägar.

Riksvägar are often of a relatively high standard and

sometimes pass through several counties. They

cover the whole of Sweden.

In Sweden, national roads with low numbers are in

the south and those with high numbers are in the

north. In 1961, the Swedish national highway system

was redesigned. Some former national roads

became European roads and are counted as a

national road with the same number as the European

road, but only the European road number is

displayed on signposts. The remaining national

roads (riksvägar), often with new routes, were re-

signed from 1962 with white numbers against a blue

background.

From 1945 to 1962, the Helsingborg-Stockholm route

was called Riksväg 1. The section to the north, i.e.

Stockholm-Haparanda, became Riksväg 13.

Nowadays this entire stretch is the E4 (Europaväg 4).

Från 1945 till 1962 hette vägen

Helsingborg–Stockholm Riksväg 1 eller Riksettan.

Sträckan norrut, dvs Stockholm–Haparanda blev

Riksväg 13 eller Rikstretton. Numera är hela denna

sträcka E4 (Europe road 4).

Regional Roads

In Sweden, a county road (Swe: länsväg) is a

government-owned public road that is not a National

road or a European road. County roads are divided

into two categories according to their importance:

primary and other county roads.

Primary county roads have a common number series

throughout Sweden and, despite the name, may

cross county borders. Primary county roads are

numbered 100-499 and the number is displayed

along the road. Other county roads have their own

number series in each county, from 500 upwards.

County District Road

In Sweden before 1891, the County district road

(Swe: Häradsväg) was a road of lesser importance

than a highway but greater than a parish road. A

county district road had to be at least 6 Swedish

cubits (3.6 metres) wide, but the distinction between

county district road and parish road was not very

well defined. Under the 1891 Road Act, both the

county district road and the parish road were

replaced by the rural road (Swe: bygdeväg).

Parish Road

A parish road (Swe: sockenväg) is a comparatively

small or narrow public road through a parish, a road

that was paid for by the parish (usually 6 Swedish

cubits wide) and that mainly served the parish's own

needs (as opposed to a highway or a county district

road). In 1895 they were officially replaced by the

rural road.

Rural Road

A rural road (Swe: Bygdeväg) is the Swedish name

for a highway with extra wide shoulders, but only

one narrower lane in the middle for cars. The aim is

to make life easier for cyclists and pedestrians. The

idea is that cyclists and pedestrians should use the

shoulders, and car drivers at meetings should be

able to use the shoulders if necessary.