Copyright © Hans Högman 2019-12-06

Mass Emigration

A new epoch in the Swedish emigration to the

United States began after the American Civil War

(1861 – 1865). The emigration from Sweden to the

United States then changed in character. The early

emigrants were enterprising people who made the

journey to the United States either alone or

together with like-minded people. After the Civil

War began an organized mass emigration up to the

beginning of the 1930’s led to 1,200,000 emigrated

Swedes.

Before 1850 families were the core of the

emigration and this lasted only until the beginning

of the 1870’s. Thereafter the number of sole

emigrants increased but entire families still

dominated the emigration from cities. Families

constituted about 30 to 40% of the city emigrants. It

was from typical rural areas like Kronoberg Län,

Småland where sole emigrants were in majority.

The early emigration had a special character; when

you left the old farm in Sweden, there were no

turning back — the future was in the New Land.

Later a supplementary emigration arose where the

emigrants went to already established relatives in

the United States. At the end of the 19th century

the period of free homestead land was over. Then

the emigrants had to settle in already cultivated

areas or work in industry. This encouraged sole

emigration but made it tougher for family

emigration.

Peaks of Swedish Emigration

There have been three major peaks in the

emigration from Sweden to the United States:

1.

1868 – 1872

2.

1880 – 1893

3.

1901 – 1914

1868 – 1872:

The first of these peaks is attributed to the years of

famine in Sweden while at the same time there was

a boom in the United States. It was primarily the

wooded districts of the Län Kristianstad in the

South up to Kopparberg and Gävleborg in the

North that was hit by the famine in 1868. About

54,000 people emigrated between 1868 and 1869

and up to 1873 another 50,000. You have to

consider that the statistic from the 1860’s are

somewhat uncertain.

1880 – 1893:

There was a recession in the United States after

1873 which affected the emigration. In 1879 there

was crisis in the sawmill industry in Sweden at the

same time as the ironwork industry had difficulties

which caused another peak in the Swedish

emigration. Then it was primarily the struck

distressed areas that had an increased emigration.

The emigrations increased tenfold from sawmill

and forestry areas like Västernorrland Län (Mid

Sweden).

The industrialism in Sweden was very well in

progress from 1880 and ahead which meant that

crises in the the industry struck hard and affected

the emigration. At the same time there were

difficulties within farming with a downward

tendency in the prices of grain.

During the 1880’s about 325,000 Swedes emigrated

to North America and another 52,000 to other

places in the world. The top years in the emigration

were 1880 – 1882 and 1887 – 1888 when there was

a boom in the United States and a large demand

for laborers. In 1882 and 1888 about 45,000

Swedes emigrated respective year.

1901 – 1914:

There was another peak in Swedish emigration in

the beginning of the 20th century. After a smaller

decline in the 1890’s emigration then increased

again. About 35,000 emigrants left Sweden in 1903.

The numbers remained high until the outbreak of

World War I in 1914. About 20% of all Swedes then

lived in the United States.

This caused a nationwide concern in Sweden and

an Emigration Commission was appointed by the

Swedish Parliament (Riksdag) in 1907 to look into

the question. The Commission recommended

social and economic reforms to restrain the

emigration.

A general strike, the so-called Storstrejken, broke

out in 1909 in Sweden. The ongoing recession

pressured many companies and SAF (The Swedish

Employers' Confederation) planned to cut wages and

salaries in certain areas. To enforce their demands,

about 80,000 employees in textile, sawmill and

paper pulp industries were locked-out at the end of

July 1909.

The answer from LO (The Swedish Trade Union

Confederation) was a general strike in all areas; a

general strike where only public medical service

and other important social and public functions

were excluded. At most there were 300,000

laborers on strike all over Sweden (the population

of Sweden at the time was about 5 million so the

number of people on strike was large). The strike

funds were small and the trade union had to

gradually reduce the extent of the strike after only a

month. This was not popular among the strikers

and caused a widespread defection from LO (the

trade union). The employers also took advantage of

the opportunity and fired about 20,000 laborers.

This also contributed to the defection from the

trade union since there was a demand from the

companies to reemploy laborers during the

ongoing strike. The strike lasted for three months.

The emigration from Sweden increased as an effect

of the strike.

The emigration stopped entirely during WW I

(1914 – 1918) but speeded up again after 1918 with

a peak before 1924. Immigration to the United

States was reduced from 1924 due to a new

legislation in the United States which required

immigrants to obtain Visa. With Visa’s issued by US

Consulate offices in their country of origin,

questions and medical inspections were done there

at the time. Done at the Consulate, there was no

longer a need for Ellis Island and other processing

stations. The new Act also contained an immigrant

quota.

The Swedish emigration to the United States was

greatly decreased by the end of the 1920’s and

almost stopped after 1930.

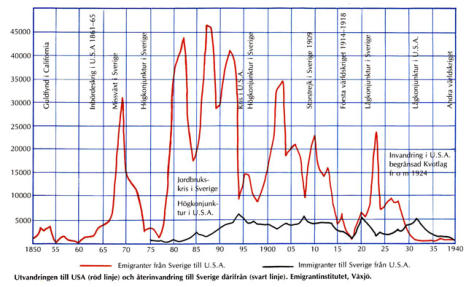

The Emigration from

Sweden to the USA (3)

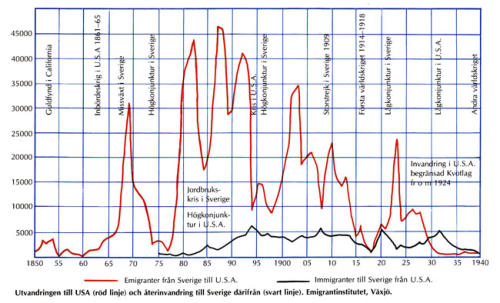

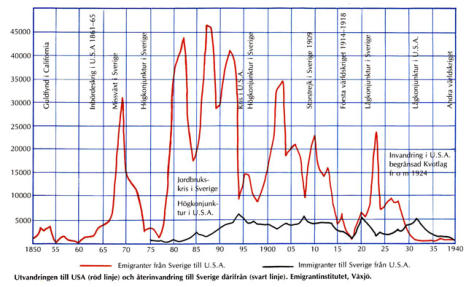

In the diagram, from Emigrantinstitutet in Växjö,

Sweden, we can see the peaks of the emigration

from Sweden to the USA (in red) but also the

returning emigrants (in black). We can also see

when there were times of recession respectively and

times of prosperity both in the USA and Sweden.

The chart covers the period from 1850 to 1940.

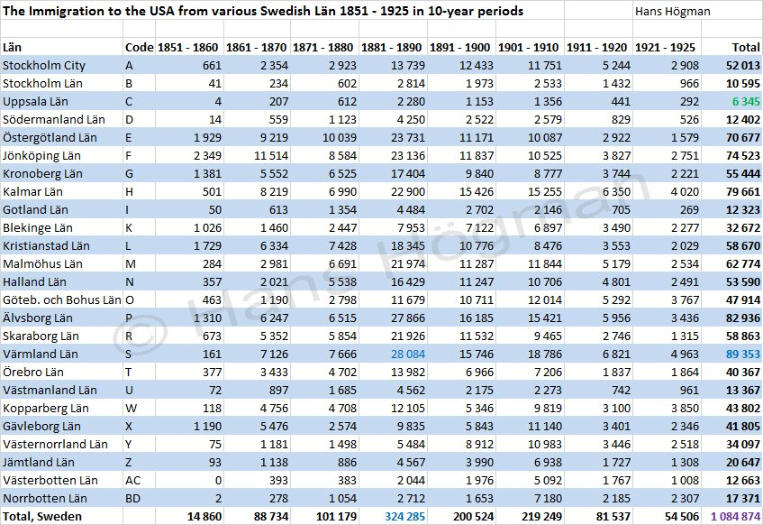

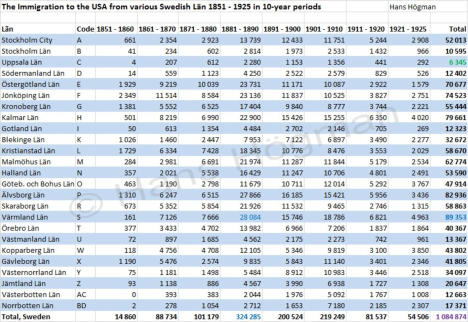

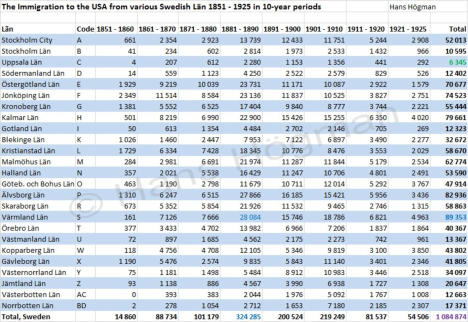

The chart above shows the emigration from

Sweden to the USA distributed per Län (region)

between 1851 and 1925. The chart shows the

number of people per decade.

The column Code shows the Län code (county code)

for respective Län.

Chart Hans Högman 2013.

Note: the space delimiter for thousands, for example

1 084 874 = 1,084,874.

See also Thousands Delimiter

and Map of the Swedish Län

The chart above is ordered by the Län Code which

means that is also ordered in geographical order

beginning in the Central east coast, down the east

side to the south of Sweden and again north on the

west side to Central Sweden. Thereafter follow the

Län in Norrland.

Län next to each other in the chart are thereby also

neighboring Län. This is the ordinary way of listing

the Län in Sweden.

If we examine the chart above we will find that the

decade that tops the emigration from Sweden is

the 1880’s when fully 324,000 Swedes emigrated.

From Värmland Län alone fully 28,000 emigrated in

the period followed by Älvsborg Län (27,866),

Östergötland Län (23,731), Jönköping Län (23,136),

Kalmar Län (22,900), Malmöhus Län (21,974) and

Skaraborg Län (21,926).

If we add together the Län in Småland province

(Jönköping Län, Kronoberg Län and Kalmar Län) we

will get 63,440 people from Småland, 49,792 from

Västergötland province and 40,319 from Skåne

province for the 1880’s.

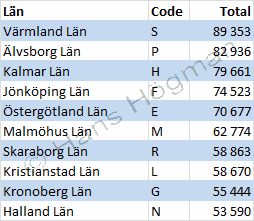

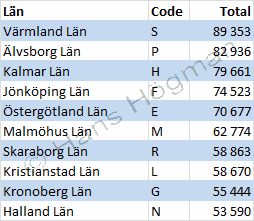

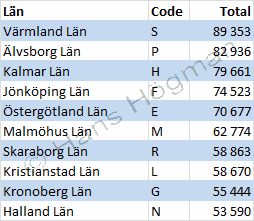

The Län that tops the chart of emigrating

Swedes, see below, is Värmland Län with fully

89,000 emigrants during the emigration period

between 1851 and 1925. The Län with the smallest

number of emigrants is Uppsala Län with only 6,000

emigrants in the period.

The province with the highest number of

emigrants is Småland (Jönköping Län, Kronoberg

Län and Kalmar Län) with a total of 209,000

emigrants.

Map of the Swedish provinces

The emigration was remarkably sensitive to economic

fluctuations. Information sent back home about the

conditions in the United States was obviously fast and

the signals about the conditions were immediately

apprehended. This has of course to do with the large

number of Swedish emigrants in the United States.

The many letters sent back home had naturally been

in proportion to this.

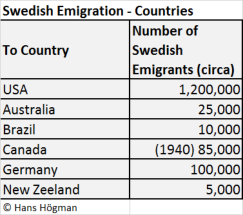

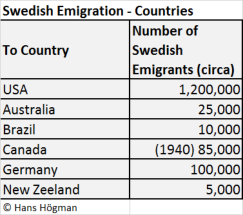

Other Countries

The Swedish emigrants not only went to the United

States but with 1,200,000 emigrants it was the major

country of the Swedish emigration.

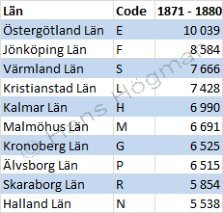

Regional Distribution of the

Emigration From Sweden

The many Swedish emigrants came from different

areas of Sweden.

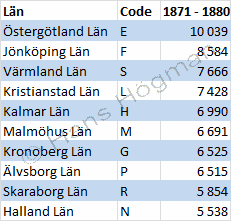

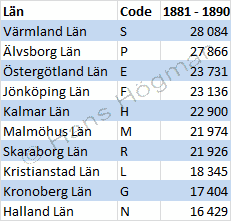

During the 1870’s the emigrants came from Län like

Östergötland, Jönköping, Värmland, Kristianstad and

Kalmar. In the 1880’s Värmland and Älvsborg Län

topped the list followed by Östergötland. See the

charts below.

The charts show the emigration from Sweden to the

USA distributed per Län (region) for the 1870's and

the 1880's.

Charts Hans Högman 2013.

Map of the Swedish Län

The chart shows the top Län in the emigration from

Sweden to the USA distributed per Län (region) for

the for the entire emigration period 1851 through

1925.

Chart Hans Högman 2013.

Map of the Swedish Län

The Norrland Region was an area that during the

first half of the 1800’s had been absorbing the

surplus population from the other parts of Sweden.

Sweden has three major regions and Norrland is the

northern region and the largest (by area) of the

three. The population of Norrland doubled during

the first half of the century. After 1850, this trend

was broken at the same time the emigration from

Jämtland Län and Norrbotten Län grew, two of the

Län in Norrland. [it is Län both in singular as well as

in plural].

See Regions of Sweden and Map of the Swedish Län

Stockholm Län and the Län around Lake Mälaren

had the lowest number of emigrants had, like

Uppsala, Västmanland and Södermanland Län. Lake

Mälaren is located just west of Stockholm. The larger

cities in this area acted as a catchment area for

laborers that been laid off from farming.

It was often they who had migrated to cities that also

emigrated from the cities. Rather than returning to

farming areas they choose to emigrate if they had

difficulties finding labor and income in the cities.

Distribution According to Sex

At first, the men dominated the emigration. The

proportion between 1851 and 1870 was 70 women

to 100 men. This later developed to an increased

balance in the distribution according to sex, not the

least when the emigration from cities grew. The

surplus of women was greater there.

Plenty of Job Opportunities in the

United States

Not only agricultural workers emigrated. In the

United States there were plenty of opportunities for

everybody willing to work. America was a nation

under development and had a great need for

laborers. This need spanned to all kinds of branches

of occupations. The Midwest had a large need for

unqualified laborers. This was about the same area

that offered free homestead land. This combination

was important since it gave the settlers an

opportunity for livelihood through temporary jobs

before they had cultivated their own land and it

became productive.

The need for lumberjacks, farm workers and

unskilled laborers was huge. Railroad construction

attracted large numbers of the workforce. As railroad

constructions progressed these job opportunities

headed west.

Another type of work was offered in the Eastern

States where industries were being developed. Large

cities like Chicago also attracted a huge labor force.

As the settling of the Midwest ended, i.e. at the end

of the 19th century, it was the cities need for

workforce that tempted the laborers, both within

industry and service occupations. Newly arrived

emigrants often worked for relatives and friends who

had emigrated earlier and settled in the new country.

Most farmers / farmhands in Sweden worked in

farming during the summer and in the forests in

winter as lumberjacks. So, a great deal of the

Swedish emigrants were experienced lumberjacks

and were appreciated in the United States. For

example many Swedes worked as loggers in the

forests of Maine.

High Salaries

It was not just the job opportunities in the United

States that attracted the Swedish emigrants but also

the high salaries. The pronounced shortage of

laborers in the expanding areas of the United States

forced up the salaries. A farm hand’s salary was for

example three times as high as in Sweden. Salaries

for skilled workers like carpenters and smiths were

even higher.

When information about these salaries reached

Sweden it had a greater “pulling-effect” than any

other emigrant propaganda.

The industrial salaries were also higher than in

Sweden. On the other hand, development for better

working conditions was not as progressive as in

Sweden.

The men among the Swedish emigrants often worked

as skilled laborers like tailors, shoemakers,

carpenters and industrial workers. Their wives sewed

in the homes and the girls served as maids for the

established Americans. At the turn of the century

1900 many of the Swedish emigrants’ lived in

suburbs of the big cities with homes of their own and

in all respects had a better social environment. An

important factor to the success of the Swedes was

their calm attitude at working sites. They were

regarded loyal and hardworking people.

Germans were often considered socialists and the

Irish troublemakers. The Swedes calmer attitude

made them often attractive for employers. The so-

called "Swedish Maids" also were highly in demand.

Age and Marital Status

The emigrants were primarily all younger people. The

largest age group were those 20 to 25 years old

followed by those 25 to 30 years old.

1.

20 – 25 years old

2.

25 – 30 years old

3.

15 – 20 years old

The average age of the emigrants in other words was

remarkably low.

The marital status among the emigrants saw a shift.

It was primarily married couples with children

that emigrated during the mass emigration era. They

constituted then 61% of all emigrants. However, the

number of families later diminished. In the beginning

of the 20th century families constituted only 28%. In

other words the number of unmarried emigrants

increased, particularly the unmarried women. One

reason for this was the need for maids and servant

girls in the United States.

Social Distribution

The majority of Swedish emigrants were non-

landowners. It is estimated that about 80% of all

emigrants from farming were non-landowners.

Among these different types of farm laborers were

sons of freehold farmers, farmhands, maids, tenant

farmers (torpare), “backstugesittare”, dependent

lodgers (inhyseshjon), agricultural laborer receiving

allowance in kind (statare) and day laborers.

The non-landowners who emigrated before the end

of the 19th century were certainly attracted by the

possibility of obtaining free Homestead land in the

United States.

Casual Jobs

It was common for the settlers to take casual jobs in

the beginning. To clear the land and cultivate the

ground required money. The settlers therefore took

casual jobs to obtain necessary capital. These jobs

could, for example, be at railroad companies that

needed laborers for the many railroad construction

projects. The Swedes earned the reputation to be the

best navvies (railroad laborers). A railroad tycoon

once said, “Give me moist snuff (snus), whiskey and

Swedes and I will build a railroad to Hell”.

Another possibility for the Swedish settlers was

logging in the forest areas. The Swedes were skilled

loggers. Large forest regions were clear-cut in

Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan during the 19th

century. The logging was rushed but gave good

income to the loggers. However, the intensive felling

caused troublesome soil erosion which still is present

in these parts of the country.

The men handed over their settlements to the

women and went logging in the forest areas during

the first two or three winters and returned in

summer to carry on with farming.

Snus:

Snus is a Swedish moist powder tobacco product

originating from a variant of dry snuff in early 18th

century Sweden. It is consumed by placing it under

the upper lip for extended periods of time. Snus does

not result in the need for spitting. In the 19th century,

Swedish producers began to manufacture moist

snus. “Ljunglöfs Ettan” (meaning "Ljunglöf Number

One"), registered since 1822, is the oldest brand of

snus still sold. The Swedish emigrants brought the

snus to their new homeland.

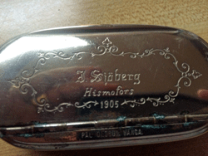

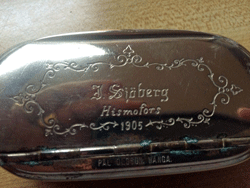

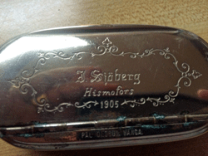

The image to the right shows a

modern snus box from Ljunglöf

Ettan.

To the left is an image of a

"snusdosa" (snuff box). In

former days' snus was

bought loose, by weight.

Therefore, most people in

Sweden had a personal

“snusdosa”, small boxes

where they had their daily ration of snus. A

“snusdosa” could be made of different materials such

as silver, steel or wood. They were often engraved. I

would say that a typical snuffbox was about 3 inches

wide.

The "snusdosa" to the left might be made of silver

and is engraved. The inscription is “J. Sjöberg,

Hismofors, 1905”. Below is another name engraved

“Pål Olsson, Wånga”.

Hismofors (modern spelling Hissmofors) referes to

Hismofors village, Rödön parish, Krokom town,

Jämtland province, Sweden. J. Sjöberg is Jöns Sjöberg,

Hismofors. Pål Olsson in Wånga (Vånga) is the maker

of the snusdosa.

There was a tobacco company in the area, Krokom

Tobacco Company which manufactured snus. The

tobacco company was located in Krokom, Rödön

parish, Jämtland. The company was established in

1871 and had about 70 employees. The company

only existed for 21 years; 1871 to 1893.

The box belongs to Sonja (Carlson) Thomas in

Orlando, Florida. This "snusdosa" came to America

with her Swedish ancestors when they immigrated to

the USA.

The image is shown with consent of Sonja Thomas.

Read the full story about the snusdosa and the

Sjöberg family

Credit

Settlers who bought land owned by the railroad

companies normally did not have to make down

payments during the first two years. The settlers

were also often offered to work for the railroad

companies during that time.

The railroad companies usually owned more land

than needed for the tracks. It could be up to 15 - 20

km (15 miles) on both sides of the tracks; therefore

they sold excess land to settlers and thereby were

able to further finance their projects.

Source References

•

Source references

Top of page