Copyright © Hans Högman 2021-07-24

Introduction

Before the modern land reforms were implemented

in Sweden, the land in the villages was divided into

different ownership systems. The common feature

of these systems was that the different farms'

properties were strongly intermingled with each

other. Preparing the land, sowing, harvesting, and

putting animals out to pasture after harvest needed

to be coordinated.

The vast majority of farmers in Sweden lived in

villages from the Middle Ages onwards and

cultivated strips of tilled land (tegar). The farmers'

strips of land were narrow and located next to each

other in the fields. The system meant that each

farmer had shares of all different types of land in the

village. But the “teg” system with strips of tilled land

required that the land was cultivated in a

coordinated way in the village, or even that sowing

and harvesting took place together with the other

farmers in the village. It was also at places so far

from the village to the outermost strips of land that

they were difficult to cultivate.

During the 18th century, thoughts and ideas about

various land reforms began to spread in Sweden.

Inspiration was drawn from England, Germany, and

Denmark, where similar reforms had already been

implemented with successful results. The basic idea

of the land reforms was to make farming more

efficient by limiting the number of fields and

meadows per farm and instead grouping the

individual farm units' properties into larger

undivided parcels.

The land reforms, mainly the "Enskifte" in Skåne and

the "Laga skifte" in the rest of the country, were of

great importance for the future development of

agriculture and resulted in increased cultivation and

grain production.

Land Reform

Land reform is a purposive change in the way in

which agricultural land is held or owned, the

methods of cultivation that are employed, or the

relation of agriculture to the rest of the economy.

Land reform may consist of a government-initiated

or government-backed land redistribution, generally

of agricultural land, or initiated by interested groups.

Land reform has become synonymous with agrarian

reform or a rapid improvement of the agrarian

structure. It also deals with the state of technology.

The Swedish land reforms didn’t aim to transfer land

ownership away from owners, but merely redistribute

the farmers’ various strips of agricultural land in a

village into larger undivided parcels per farmer.

The Swedish term for land reform is

“Skiftesreform”.

Rural Agricultural Villages

Village (Swe: By) may denote a named place

consisting of at least two neighbouring farms and

possibly several crofts in the countryside, but was

also a legal designation for a collection of farms that

are or have been a community for the common

ownership and use of certain land or forest - so-called

commons (farming villages). This latter definition

applied before the land reform of the early

nineteenth century to Swedish and Finnish land

parcels shared by several farms. The term is used

primarily for agricultural villages. In a terraced

village (Swe: radby), the farms are arranged in a row,

usually along the village street. With the land reform

of the 19th century, most of the row villages

disappeared.

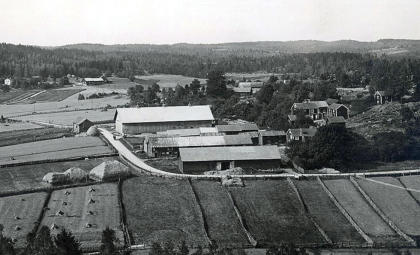

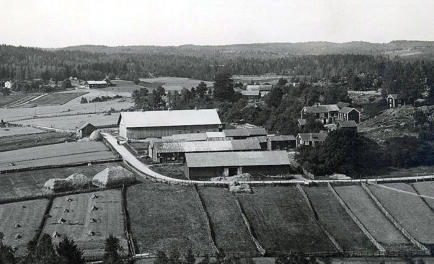

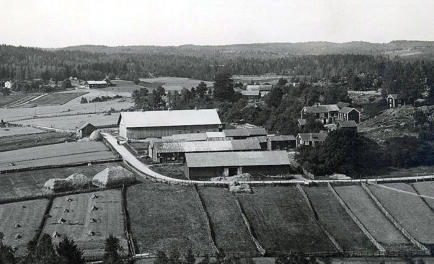

The image to

the right shows

a view from a

terraced village

(Swe: radby) in

Eriksöre, Kalmar

County, in 1900.

Image: Kalmar

Läns Museum.

ID: KLMF.A01558.

In the agricultural villages, the land was arranged

in parcels called "tegskifte". This meant that the

different landowners of the village (Swe: byamän)

were clearly defined, as well as the share each of

them had in the village.

Based on this key, the village plot of land (where the

farm buildings were located) was divided into legal

shares, as were the cultivated fields. The meadow

(where the hay was harvested) and the pasture were

common (shared between the farmers in the village),

but the sharing key defined how much of the hay

would go to each person and how much livestock

each person could have on the pasture.

This is called “tegskifte” in Swedish and the strips of

tilled land established by the distribution of

farmland are called ”tegar” (plural).

People who were not joint owners of the village had

to pay to build houses on the village land or use the

pasture.

In the 1734 law, the first chapter of the “Bygninga

Balken” (Village Section) defined "How the plot of land

for a village shall be laid out, and farmland

distributed". The law stipulated that every part of the

village area was to be divided among all the co-

owners (Swe: Byamännen). Furthermore, the

individual farmsteads’ strips of tilled land (Swe:

tegar) were to be laid out in the relation to each

other in the same way as the farms were adjacent to

each other in the village.

Village Council

It was usually the village council (bystämman) that

administered and managed the strips of tilled land.

The village council was headed by a village elder

(Byålderman) appointed by the “byamännen” (the

landed people in the village) to manage the village's

farm activities, and the village rules were written

down in a Village Ordinance (Byordning). The

members of the council are called the “Byalaget”

(Village Councilors) or “Byarådet”.

The members of the village council are those who

own land in the village (more than just a plot) and

were, therefore the owners of agricultural property.

The village council governed the village according to

customary law, often codified in a specially written

village ordinance (byordning), a statute on common

affairs laid down by the district court of law. The

village elder is elected by merit or in order according

to a rotation system. The most important meeting of

the year is usually held around Walpurgis Eve and is

called the May Meeting.

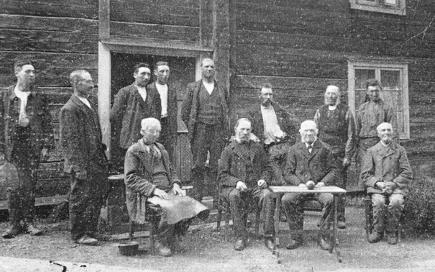

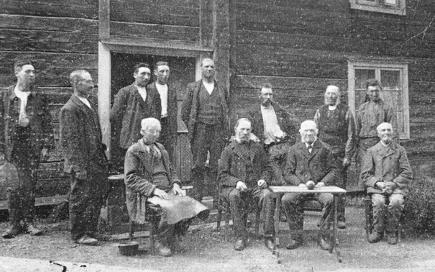

The image to the right shows village councillors of

Kila village, Hycklinge parish, Östergötland County, at

a village council meeting. Photo: Sigurd Erixon.

Image: Wikipedia.

A village ordinance (byordning) mainly contained

rules on livestock and fencing (of central importance

before the Laga Skifte land reform change in the 19th

century). The use of the common property (mills,

sandpits, peat quarries, fishing waters) was also

regulated in the village ordinances, as were often fire

protection, poor relief issues, the relationship

between the propertied and non-propertied

villagers, and even certain moral issues. The village

council could levy fines for breaches of the village

ordinance. Sometimes the village dealt with matters

that were usually within the jurisdiction of the parish

council.

The villages were often also inhabited by crofters,

tenants, and others who lived on houses that stand

on other’s freehold ground. These people were not

involved in decisions concerning the mutual affairs

of the village and did not have the right to vote at

the village council meeting.

To achieve greater uniformity in the village councils'

ordinances, the government issued an Act called

“Mönsterbyordning” (Model Village Ordinance) in

1742.

The construction and maintenance of fences (Swe:

gärdsgård) was important and carefully prescribed by

law. The fences were there to prevent the livestock

or wild animals from entering the fields and

destroying the crops. All fields were therefore

fenced. Each homestead in the village was assigned

a section of the fenced farmland for which it was

responsible, and the fences were usually inspected

twice a year. There were also fences around the

pastures to prevent animals from escaping or

entering the cultivation fields. Both at the cultivation

fields and the pastures there were gates in the

fences and everyone who passed a gate needed to

close it behind them. It was not uncommon for a

public road to run through the pasture and thus

wayfarers had to pass many gates to be opened and

closed.

When it was time to sow or harvest, this had to be

done at the same time on all strips of tilled land, as

many farmer's strips could not be accessed without

first passing through others. This meant that every

farm in the village had to have the soil prepared in

time for everyone to sow on the day set by the

village council. This also applied to harvesting, of

course. Similar rules applied to the hay-making of

meadows. Furthermore, the hay had to be put in by

a certain day, after which the cattle were usually let

out to graze on the meadows.

History of Agriculture

Agriculture originated 12,000 years ago in several

independent locations.

Different crops were exploited in each location,

which meant that the trade networks that later

emerged could spread developed crops to new

markets. In the Middle East and Europe, wheat

became the most important crop, in Asia rice and

millet were grown, and in America maize, cassava,

beans, and potatoes. Agriculture produced a surplus

that both increased the population and gave rise to

the first city-states.

Around 10,000 years BC, people lived as hunters and

gatherers. The transformation of people's lives

brought about by agriculture had revolutionary

consequences and is often referred to as the

Neolithic Revolution. Agriculture meant an increased

availability of food, which in turn meant rapid

population growth and larger permanent

settlements. These settlements developed into the

first city-states.

Because agriculture produced a surplus, this surplus

could be exchanged for other goods. Surplus and

trade meant that some groups of people could earn

a living in ways other than farming, such as crafts.

Surpluses were also used to pay for common goods:

defenses, churches, irrigation. While this led to

increased specialization, it also led to increased

stratification.

Agriculture came to Sweden from the continent

around 4,000 years BC. It seems to have been a

rapid process (not measurable with the 14C

method). It seems that indigenous Mesolithic groups

take up the so-called funnel beam culture. This was

the first farming culture in the Nordic countries.

During the European Middle Ages, there were many

advances in agriculture.

In the 700s, the introduction of the bow wood from

Asia made it possible to use horses to pull heavy

loads. The horses could be used to plow the land;

previously oxen had been used for this as the horses

were strangled by the harness. The wheeled plow

was an even more important invention, especially in

heavy soil.

The image to the

right shows a

farmer with a

wheeled plow.

Image: Wikipedia.

In much of Europe, the three-year rotation (three-

field system) was introduced, which meant that

each field was cultivated one year with spring grain

(such as oats), one year with winter grain, and left

fallow only every third year. During the fallow period,

the land was fertilized by livestock. This increased

production and since there were two harvests, there

was less risk of crop failure. Up until the 1300s, the

grain rate (the ratio of the harvest to seed) rose

sharply. The next major increase would not occur

until the 18th century, because in the early modern

period there were no major changes in agriculture

except for the growth of farming units and a more

market-oriented approach to production.

The Agrarian Revolution

The Agrarian Revolution is an agricultural

revolution that is said to have taken place in the late

18th century in Western Europe, particularly in

England and France. It later spread to other

countries. In Sweden, it corresponded to several

successive land reforms in the late 18th and early

19th centuries. Agrarian comes from the Latin word

for the field, ager.

Towards the end of the 18th century, major changes

took place in agriculture. For a long time, farmers

had been cultivating several but small tilled strips of

land. These small strips were now merged into

larger fields. This made it easier for farmers to plow

large fields at once. Harrows and seed drills made

the heavy farming work easier, leading to more

rational work. This meant that fewer people had to

work in the fields.

Crop rotation (Swe: växelbruk) was also introduced

in agriculture. Previously, a third of the land had

been left fallow to avoid depletion. But with crop

rotation, barley and wheat were grown every other

year and forage, such as clover and peas, every

other year. The forage supplied the fields with

nitrogen from the air. The forage gave the animals

better feed and allowed them to produce more food.

The agrarian revolution led to a significant increase

in food production and required less labor than

before.

Similarly, in Sweden, the so-called "Storskiftet" (The

Great Land Reform) was carried out just before the

turn of the century 1800, as well as the "Laga

Skiftet" in the middle of the 19th century. This led,

among other things, to the disappearance of many

of the old terraced farming villages (radbyar), in favor

of individually situated farms with contiguous

landholdings.

Older Agricultural Land Reforms

Hammarskifte

Hammarskifte is the oldest known form of property

settlement in the Swedish farming villages before

the Solskiftet (see below).

Despite many studies, it is not known what the

Hammarskifte actually meant. The name comes from

the Uppland Law of 1296, which stipulates that all

land must be laid in Solskifte and not in “hambri” and

in “forni skipt”, which led to the assumption that the

Hammarskifte is the same as “fornt skifte”, the land

tenure system that applied before the introduction

of Solskifte. Parallels have also been drawn between

the Hammarskifte and Bolskifte in Skåne (South

Sweden), but in the South Swedish provinces’ village

organization has much older traditions than in

Svealand (Central Sweden) and it is doubtful

whether these concepts were synonyms.

Based on preserved structures, agriculture in the

Iron Age, to the extent that villages existed, does not

seem to have had strips of tilled land in the true

sense, but only a form of organization. Grazing was

common to the farms in the village, while the farms'

arable fields were separated from each other.

Hammarskifte, is a term that appears in some of the

medieval provincial building laws (Uppland Law,

Västman Law, and Södermanland Law).

Tegskifte

The Tegskifte was first called hammarskifte or

bolskifte (in Skåne), and later also solskifte. The village

land was divided so that the co-owners, each in

proportion to their share, received an equal amount

of land in all the scattered, often disparate, property

parcels. This was done without any so-called grading

(grading refers to the valuation of land according to

its yield potential. The land was given a certain grade

so that a larger area of poorer quality land was given

in exchange for a certain area of better quality.)

Tegskifte was the form of land tenure previously

used in large parts of Europe and in Sweden (in

Sweden until the Storskifte land reform in 1749 and

1757). Tegskifte meant that each farm in a village was

allocated its share of the village farmland. A farm's

share in the village could be different from others.

This meant that the farms received as much of the

village land as their share entitled them to. The basic

principle of the tegskifte was that no farm would

benefit more than others, but it is a common

misconception that this would mean total fairness

between a village's farms.

The system worked relatively well in the early days,

but as the population grew and farms were split over

and over due to inheritance divisions, often over

many generations, the Tegskifte system became very

impractical over time. Another problem was that a

large amount of work was required to move oneself

and one's tools between each strip of acres.

Over time, the tegskifte became so inefficient that the

government was forced to implement major land

reforms in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

However, no compulsory national land reform was ever

carried out. Both the storskifte and the laga skifte were

based on a land reform notification from at least one of

the village's farmers.

If a farmer had made such a notification, the rest of

the village's farmers had to participate in the land

reform, which often contributed to discord between

villagers. This meant that many farmers felt

disadvantaged compared to the tegskifte system, as

some could be allocated fields with good soil quality

and fertility while others could be allocated poorer

soil.

It also led to the fragmentation of many villages in

the great plains as farmers were forced to move

their dwellings, out of the village, to their new more

contiguous estates.

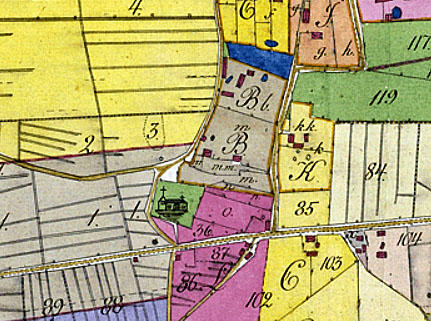

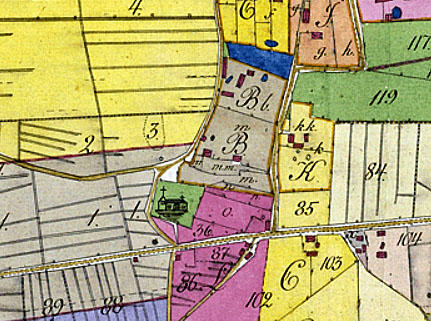

The image is an

aerial view of the

village of Gillberga

with all the strips of

acres and meadows

around the village.

Image: Kalmar Läns

Museum. ID:

KLMF.D00054.

Tegskifte is a generic

term for the various ancient forms of division -

usually in narrow strips, so-called tegar - of fields and

meadows between the various farms within the

common boundaries of the villages. The strips of

tilled land were mixed, i.e. they were more or less

systematically mixed and cultivated individually by

their owners in an annual rhythm common to the

village community. The solskifte (sun system) was a

systematic form of the tegskifte. The tegskifte

system, which was common before the reforms of

the 18th and 19th centuries, gave the farms a share

in all the different types of land and soil in the

village. It was not until the enskifte (single parcel

system) and the laga skifte that the fertility of the soil

was weighed against the size of the surface of the

parcels when implementing the land reforms.

Solskiftet

The Solskifte System was a land tenure system

that developed in the early middle ages but was

formalized in Swedish law around 1350. Solskifte

means Solar distribution of farmland and is a way of

allocating land within the community, such that each

farmer gets equal access to the sun through the

year.

The Solskifte meant the laying out of rectangular

farming village plots as single or double terraced

villages. The width of the farm plot was determined

by the size of the farm or its share in the village. The

farm that was located first in the village always had

the first strip of tilled land in the acres in the same

relative position as the farm plot in the village, hence

the name 'solskifte'. The farm whose plot was

furthest to the south thus also had its strips to the

south in each strip of the tilled land. Solskiftet

referred to both cultivated land and the

redistribution of the previously common land of

fields and meadows.

These strips of tilled land were common in eastern

Central Sweden, where the width and order of the

rows followed an agreed pattern. The Uppland Law

stipulates Solskifte and in Magnus Eriksson's

National Law Code of 1350, it is laid down for the

whole of Sweden, although in practice it never

spread outside Central Sweden.

Solskifte got its name from the principle of order

that applied when the strips of tilled land were laid

out: each farm got its strip in the same relative

position as the farm plot in the village so that the

farm whose plot was furthest south or east on the

village plot also got its strips in the south and east in

each set of strips.

In this method of tenure, a community was

composed of a village and the surrounding lands.

Agricultural Land Reforms,

Sweden (1)

Storskifte Land Reform in 1749

and 1757

The first modern land reform in Sweden was the

"storskifte" (The Great Land Reform or The Great

Partition / The Great Land Redistribution).

Storskifte was a land reform supported by the

government enabling the division of the farmland of

the village communities, from the former Solskifte

system to a new system, where every farmer in the

village was to own connected pieces of farmland

instead of several scattered strips of land.

Under the law of 1734, a new division or

redistribution of the farmland could not take place

unless all the landowners in the village agreed to it.

The land reform was initiated by the Riksdag

(Parliament) with the 1749 Land Survey Act, and later

in 1757 with a decree called the "Storskifte", which

introduced the "land reform warrant" (i.e. the land

reform was to be executed if one landowner in the

village requested it). This made it possible for a co-

owner of the village farmland to request

redistribution of land (skifte), which then also

included the other landowners' shares of the

farmland, i.e. an attempt to gather the farmers'

several strips of land into larger coherent parcels.

Storskifte was carried out in large parts of the

country between 1758 and 1827.

The land reform had two main objectives:

1.

To consolidate the fields and meadows into fewer

units.

2.

To divide the jointly owned land between the

farmers to improve its use.

In other words, the reform involved the

redistribution of land ownership in rural villages. The

target set in 1762 was a maximum of four pieces of

arable land and an equal number of meadows per

farm, but this target was not always met, not even in

later lands reforms.

From 1783, individual farms could request complete

separation and relocation from the village, a

precursor to the 1803 Enskifte land reform. Such

relocation of farmhouses (onto each farmer’s

allocated land) was preceded by a property valuation

and land grading, with the size of land weighed

against the quality of the land.

The Storskifte land reform was inspired by similar

land reform in England involving land redistribution.

Enskifte Land Reform

As can be seen from the Storskifte section above, the

goal of fewer and larger parcels was not always

achieved. King Gustav IV Adolf, therefore, issued the

Ordinance on Enskifte, which meant that each

farmer's land should be combined into one single

piece of farmland if possible. The enskifte began to

be implemented in Sweden in the late 18th and

early 19th centuries.

Enskifte was the second modern land reform and was

initiated by Rutger Macklean at the Svaneholm

estate in Skåne. Inspired by the land reforms carried

out in England and Denmark, Macklean already

implemented a major land redistribution on his

Svaneholm estate in the late 18th century, despite

strong opposition from the peasants. In several of

villages under the estate, a very strict redistribution

of land was then implemented, which meant that the

scattered land of the farming units had to be brought

together in one larger parcel, enskifte, which meant

that the old villages were split up. In many cases, the

farmers had to move their farmhouses or build new

ones within the

boundaries of the new

coherent parcels.

The image shows

Svaneholms estate in

Skurup, Skåne, in 2008.

Image: Wikipedia.

As the reform showed

that both productivity and profitability increased, a

decree was issued in 1803 by the government on the

implementation of the enskifte in the whole of

Skåne, in the county of Skaraborg in 1804 and the

whole kingdom in 1807, except for the counties of

Kopparberg, Gävleborg, Västernorrland and

Västerbotten, and Finland. In principle, the northern

parts of the country were excluded.

Some farmers had to leave their village plot to build

a new farmhouse on the allocated land, others had

the opportunity to stay. The enskifte redistribution of

farmland was not only initiated by owners of landed

estates but was also carried out in villages with

freehold farmers. A prerequisite for the success of

enskifte was that the land was equal and fertile and

that almost all the land could be cultivated. This

meant that the enskifte system was most

widespread in the plains of Skåne and Västergötland

and on Öland.

The enskifte followed the great land reform,

Storskifte, but was much more radical. It was in turn

followed by the Laga skifte reform of 1827 since the

expected results were not achieved. As the Storskifte

and the Enskifte were practiced in parallel in the

country, difficulties arose in consistently

implementing the reform of the Enskifte. Enskifte

literally means “one parcel”.

Laga skifte Land Reform in 1827

During the reign of King Karl XIV Johan, the land

reform could be carried out more systematically. In

1827, the law on the Laga skifte (Skiftesstadgan) was

passed, but it was carried out at different times

around the country. The principles of this statute

remained in force until 1928. It was partially revised

in 1866 and replaced by the 1926 Act on the division

of land, which came into force on 1 January 1928. The

name of the Act, Laga Skifte, implies that the land

reform was legally supported.

The objective of the Laga skifte was to some extent

the same as that of the reform of the Enskifte; the

aim was to combine the landowners' farmland into

as few parcels as possible. The Laga skifte

determined that a farming unit could comprise a

maximum of three parcels of land.

Every co-owner of a village could, according to the

1827 Laga skifte Act (land reform Act), request

redistribution of the parcels of land, and

redistribution could be carried out of land belonging

to a village or homestead in which two or more

people had a share. In principle, the redistribution

would cover all types of land.

At the time of the redistribution settlement, a

property valuation would be made to obtain a fair

distribution of the land. The landowner who was

allocated land of poorer quality at the time of the

land redistribution could be compensated by

receiving a larger area. The total value of the

homestead before and after the division would be

equal.

The image shows the village of Väsby in Östergötland

in 1898. The strips of tilled land in this village have

not been redistributed in the land reforms as can

been seen in the photo. Image: Wikipedia.

For all farmers to receive their rightful share of the

land, previously uncultivated land also had to be

distributed among the farmers, which for many

meant labor-intensive new cultivations. To cultivate

the new land, some farmers were required to move

out (utflyttningsskyldighet), which meant moving the

farm (farmhouse, outbuildings, etc.) from the village

plot. Many of the village farmhouses, X-joint

loghouses, were therefore dismantled and rebuilt on

the location of the respective farmer’s newly

allocated land.

As farms were relocated, the village centers were

broken up, i.e. split. However, some farms remained

in their original location.

The land redistribution including the relocation of

farms meant that farmers no longer were dependent

on each other in the same way as they previously

been in the villages, and they no longer had to cross

someone else's field to get to their own.

In parts of Sweden, the land reform was never

carried out, especially not in Dalarna.

When land redistribution was to be carried out in a

village, a land surveyor was sent to measure the

farmers' land, distribute it, and draw up land

redistribution maps (skifteskartor).

However, many farmers did not want to know about

any redistribution of the parcels. It is said that in

some cases the peasants were so angry with the

surveyors that they had to carry a gun to protect

themselves.

Disputes concerning the distribution of parcels were

to be dealt with in the first instance by a newly

created court, the Property-Dividing Court

(Ägodelningsrätten).

In 1970, the 1926 Land Division Act was replaced by

the Land Consolidation Act, which entered into force

on 1 January 1972. This abolished the concept of

"Laga skifte" in Swedish property law.

Summary

The Storskifte land reform brought about a

redistribution of farmland and meadows to fewer,

larger coherent acres. The Enskifte land reform

means that an attempt was made to combine the

landholdings of each farm into a single unit, a single

parcel of land. The Laga skifte meant combining the

landowners' farmland into as few parcels of land as

possible.

The Storskifte covered only the village's infields

(inägomark), i.e. the fields and meadows closest to

the village. The outlying fields (Utmarken), often in the

form of a wooded pasture, were to be retained as

jointly owned land.

Usually, it is the boundaries from the Laga skifte that

we can see around today’s countryside.

Land Redistribution Maps

Land redistribution maps (land surveying maps) were

drawn up in connection with the land distribution of

farmland in each village. The oldest hand-drawn

maps were produced in only one copy each.

The National Land Survey of Sweden (Lantmäteriet)

later established regional offices and then the

instruction was changed, so that the surveyor, from

the basic or concept map he had drawn up, was

obliged to make a fair copy - a so-called renovation.

The fair copy of the drawing was to be delivered to

the central office in Stockholm for review. Most

survey files/maps were produced in triplicate.

The first copy was kept at the regional agency under

the term “concept”. The second copy remained with

the owner/village council (Byalaget) and the third

copy - the renovation - was sent to the central agency

in Stockholm for review. The village depended on

receiving the redistribution maps and documents.

Each shareholder in the village also received extracts

of the map and partition description relating to his

lot.

There are many documents left in village council

coffers, farm archives, and old chiffoniers!

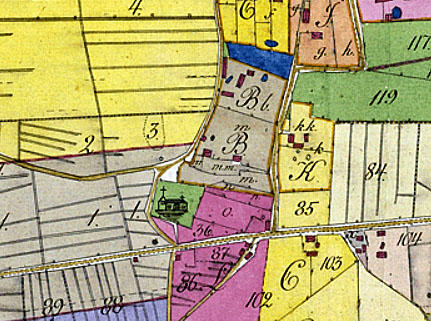

Map scales were usually 1:4 000 (100 m, in reality,

corresponds to 25 mm on the map) for the infield

areas (arable and meadow land) and 1:8 000 for the

outlying areas (forest land). The land redistribution

maps may look different, as no fixed templates were

used until after 1850. The land maps are based on

the village as the principle of division. The map is

accompanied by a description explaining the

numbers and lettering on it. Lower-case letters are

used to mark the old farm fields, capital letters for

the new ones. The boundaries are drawn in black

and red.

Note that the maps provide both a snapshot and an

indication of a desired future state. Red lines usually

indicate the boundaries that the redistribution is

intended to establish. Also, some roads and common

areas are intended to be constructed after the

redistribution of the land is completed. Please note

that changes due to appeals may occur!

The land redistribution documents contain

minutes, listing the names and residences of those

present, and annexes, including appeals, and a

description of the redistribution. It shows how the

land was distributed before the division, the grading

of the farmland, and the description of the division of

the various letters (capital letters) of the new parcels.

The various colors on the maps represent different

types of land (soil). Fields tend to be yellow, pastures

light green, meadows dark green and, water blue.

There are some variations on this and therefore you

should check with what the description says. There

you can make sure which colors represent which

types of land.

The numbers on the map: the farmlands on the

map are subdivided into smaller parts depending,

among other things, on soil conditions such as

moisture, fertility, etc. Each such area has a number

and that number refers to the charts that appear in

the description of the map.

The Land Survey Agency (Lantmäteriet) has an

extensive archive of maps drawn up during the

various land reforms carried out in Sweden from the

mid-18th century to the early 20th century. The maps

and their accompanying texts are decision-making

documents that are still partly relevant today.

Related Links

•

Terminology - Land reforms

•

Land Redistribution Maps, Laga Skifte, Kumla

village, 1833, Toresund Parish

•

Agricultural Yields and Years of Famine

•

The Old Agricultural Society and its People

•

The Concept of Mantal etc.

•

Landownership - Farmers & Crofters

•

Crofts and Crofters

•

Summer Pasture

•

The "Statar" system (keeping farm laborers

receiving allowance in kind)

•

The Concept of the Socknen (parish)

•

Property Designations - Sweden

Source References

•

Skiftesreformer i Sverige; Stor-, en- och laga

skifte, Örjan Jonsson JK92/96.

•

De stora förändringarna, 23 Enskiftet och laga

skiftet.

•

Skiftenas skede, laga skiftets handlingar som

källmaterial för byggnadshistoriska studier med

exempel från Småland 1828–1927. Ander

Franzén, 2008.

•

Tegskiftet s. 112-114 i Gadd, Carl-Johan (2000).

Det svenska jordbrukets historia. Kapitel 8, Band

3, Den agrara revolutionen : 1700-1870.

Stockholm: Natur och kultur/LT i samarbete med

Nordiska museet och Stift. Stiftelsen Lagersberg.

•

Bilden av skiftet måste nyanseras, artikel i

tidningen Populär Historia i september 2003 av

Fredrik Bergman, Larserik Tobiasson.

•

Skiftena förändrade Sverige, artikel i tidningen

Släkthistoria i mars 2017 av Therese Safstrom.

•

Lantmäteriet (The National Land Survey of

Sweden)

•

Wikipedia

•

Nationalencyklopedin (Swedish National

Encyclopedia)

•

SAOB (Svenska Akademins Ordbok - The

Swedish Academy Dictionary)

Top of Page