Copyright © Hans Högman 2021-09-10

Health Care in the Past - Sweden

Childbirth and Midwifery

In the past, all babies were born at home with the

help of a skilled local woman. In Sweden, she was

called a “jordemor” and was the midwife of the

time. A “jordemor” had no formal medical training,

but was an elderly 'wise woman' with experience

and knowledge of childbirth, often passed on from

mother to daughter. The modern term in Sweden

for midwife is “barnmorska”.

Childbirth and childhood illnesses were not without

problems, especially when medical care was not

available. It was not uncommon for pregnant

women to die in childbirth (“död i barnsäng”). One

reason for this was pre-eclampsia (Swe:

havandeskapsförgiftning), which led to high blood

pressure and often a significant amount of protein

in the urine (Swe: äggvita i urinen), which was

serious.

Other complications were cephalopelvic

disproportion, CPD, (Swe: bäckenförträngning) and

exsanguination (Swe: förblödning). After delivery,

infections such as puerperal fever (Swe:

barnsängsfeber) were a problem. In 1750, about 1%

of women delivered died, while in 1850 the figure

was down to 0.5%.

As early as 1708, a form of midwifery training

(barnmorskeutbildning) was started in Stockholm by

the physician Johan von Hoorn, and around 1711 a

midwives' guild was formed. However, before the

opening of the Seraphim Hospital in 1752, a

midwife could only graduate as an apprentice to a

professional colleague. According to the Stockholm

regulations of 1711, the prospective midwife had to

spend at least two years as an apprentice, then

report to a physician and be evaluated by him to

find out whether she was "tenable and capable".

After the apprenticeship, she was graduated from

the Collegium Medicum (A designation for medical

societies with the purpose of supervising the

medical profession).

Towns and cities were urged in 1750 to keep at

least 1 trained midwife. The training was to take

place in Stockholm. However, the licensing

requirement for rural midwives was abolished at

the request of the peasantry just three years later

because the rural parishes did not want to pay for

their midwives to travel to Stockholm.

In Gothenburg and Lund, midwifery training was

introduced at the end of the 18th century. In

Stockholm, the Pro Patria Maternity Hospital

opened in 1774 and the General Maternity Hospital

(Allmänna Barnbördshuset) in 1775, while in

Gothenburg, the Sahlgrenska Hospital opened in

1782 with a maternity ward. The maternity

hospitals (BB) also functioned as training units for

both physicians and midwives.

After childbirth, the mother had to rest and the

Churching of the woman delivered could only take

place until after 6 weeks. Then she was considered

"pure" after childbirth and could be readmitted to

the congregation.

Puerperal fever or childbed fever (barnsängsfeber)

was a bacterial infection that could affect newly

delivered women, usually caused by poor hygiene

during delivery, such as unclean hands and

instruments. The affected woman developed sepsis

(blodförgiftning ) with high fever and rapidly

deteriorating general condition. The mortality rate

was high. When it was realized that higher hygiene

in childbirth was of paramount importance, the risk

of childbed fever decreased significantly. In the

mid-19th century, several discoveries pointed to the

importance of cleanliness in childbirth, for example

in Austria. In Sweden, in 1870, physician Wilhelm

Netzel at the General Maternity Hospital (Allmänna

Barnbördshuset) in Stockholm confirmed that fever

was spread by midwives and doctors carrying

unclean instruments with organic substances. The

hygienic procedures he introduced had a good

effect. In 1879, procedures were tightened and

midwives were required to wash their hands in a

solution of carbolic acid (Phenol) before performing

procedures. For most of the 19th century, science

was aware that bacteria caused many diseases.

Despite this, anti-bacterial treatments were not

available.

In 1867, Englishman Joseph Lister published an

article on antiseptic wound treatment in The

Lancet.

Infant mortality was high. In the mid-17th century,

about one-third of all children died before the age

of 5. By the mid-19th century, however, the figure

was down to a quarter, but that must still be

considered high. An overriding cause was a

nutritional deficiency and poor nutritional status

(often protein deficiency).

In years of famine, this was evident. Pneumonia and

diarrhea diseases were common causes of death.

Diarrhea caused dehydration. Dysentery was a

bacterial intestinal infection that caused severe

bloody diarrhea. Malnutrition combined with

common infections could be devastating for

children. Measles is a viral infection that is normally

not dangerous but which, combined with

malnutrition and poor immunity, could lead to

death. Before antibiotics were available, scarlet

fever could lead to serious and fatal infections.

Physicians

A physician is a person who has graduated from a

university medical school after completing a

professional program. Thereafter, the graduate can

be employed as a doctor. At the beginning of the

19th century, there were about 200 doctors

qualified in Sweden.

In 1800, the population of Sweden was 2,347,303

(Source: SCB).

Physicians existed early in Sweden but they lived in

the cities and were for the rich. Furthermore, their

knowledge was very limited by today’s standard

and no effective medicines such as antibiotics were

available.

Rural areas were largely lacking competent

medical staff. Only in exceptional cases could a

town surgeon or field surgeon be persuaded to

make an arduous and costly journey to see

someone sick in a village.

Instead, peasant society had to rely on old

household remedies that were often mixed with a

large portion of superstition.

It was usually the parish minister or his wife who

had to respond to the sick call, and in the saddle

pocket, the parish minister had suitable medicines

alongside the communion vessels, intended for the

sick person on his deathbed.

The first provincial physicians (provinsialläkare)

began their activities at the end of the 17th century.

In 1774, these activities were nationalized. There

were then 32 provincial physicians, all based in the

towns.

In 1732, when professor Linnaeus made his

Lapland journey, he passed the northernmost

dispensary in the city of Gävle and was the last

provincial physician in the north.

A Provincial physician was a position for medical

officers who acted as district physicians. The title

has been used since the 17th century for

government, especially established medical posts.

An instruction for provincial physicians was issued

in 1744, but the services were only given a fixed

organization by the 1773 Medical Act.

The number of provincial physicians was then 32.

Such services were then (with some exceptions)

available in all the county seats of Sweden. In 1890,

there were 211 provincial physicians and 73 district

physicians (not government physicians) in Sweden.

Provincial physicians thus had a specific station

(place of stationing) and district of service, and their

task was to assist the public with private medical

care. Extra provincial physicians had the same duty

as regular provincial physicians but were paid in full

or in part by municipalities. In each county, there

was also a head provincial physician, paid by the

government, with overall responsibility for the

county's general health care.

In 1973, the term "provincial physician"

(provinsialläkare) was replaced by "district physician"

(distriktsläkare).

Nurses

Nursing education began in 1884 at

Sophiahemmet in Stockholm.

Sophiahemmet opened on 1 October 1889 in

Östermalm, Stockholm. The construction of the

hospital was made possible by a donation from

King Oscar II and his consort Queen Sophia, and

the hospital was named after Queen Sophia.

Sophiahemmet then became Sweden's first private

hospital with a total of 60-70 beds. The hospital

contained housing for 40-50 nurses.

The activities of the Sophiahemmet go back to the

foundation of the "Home for Nurses", which was

inaugurated by Queen Sophia on 1 January 1884.

The aim was to train

nurses.

The image to the right

shows Sophiahemmet

(Sophia Hospital) in

Stockholm in 2006.

Image: Wikipedia.

A nurse trained at Sophiahemmet is called a

"Sophia sister" and they are well known for

maintaining an established uniform, which includes

an apron and cap.

The length of nursing education has historically

varied between one and a half and three years. In

Sweden, professional licensing for

nurses was introduced in 1960, and

the professional title then became

certified nurse (legitimerad

sjuksköterska).

The image to the left shows a so-

called Sophia sister (nurse)

sometime between 1889 and1915.

Image: Wikipedia.

One nurse who has made a great impression in

history is the English woman Florence Nightingale

(1820 - 1910). She is known for her efforts during

the Crimean War (1853 - 1856) where she worked at

a cottage hospital. She succeeded in reducing the

mortality rate in military hospitals in Crimea from

around 42% to 2% by improving the unhygienic

conditions in the hospitals. In 1860 she founded the

Nightingale School of Nursing for nurses in London.

Her work was to influence the work of nurses

around the world.

Hospitals

A hospital (Swe: sjukhus) is an establishment for

primarily inpatient care. An older Swedish term is

“lasarett” (General hospital). Sweden's earliest

monastic hospitals were called “helgeandshus” or

“hospital” and were usually a common gathering

place for the poor and crippled as well as the

mentally and somatically ill of all kinds. Royal

decrees in 1765 and 1776 ordained that county

hospitals (länslasarett) should be established

throughout the realm in combination with special

“kurhus” wards (treatment of venereal diseases).

The image to the right shows

a hospital ward in the past.

Photo Hans Högman, 1998.

Medicinhistoriska museet,

Stockholm (Medical History

Museum).

The first hospital in

Scandinavia, the Akademiska sjukhuset (the

Uppsala University Hospital), was opened in

Uppsala in 1708. In the 1750s there were 6 beds,

and by the turn of the 1800s, the hospital was able

to take 10 patients for clinical care.

In 1752, the Serafimerlasarettet (the Seraphim

Hospital) was inaugurated on Kungsholmen in

Stockholm. The hospital was the first proper

institution in Sweden, dedicated exclusively to the

cure of diseases. It was also the first teaching

hospital in the country. The hospital initially had

only eight beds, but by 1765 the number of beds

had grown to 44.

In Stockholm, Allmänna Barnbördshuset (the

General Maternity Hospital) opened in 1775. At the

time of its opening, it had 17 beds. The maternity

hospitals (abbreviated BB in Swedish) also served

as training units for both doctors and midwives.

In Gothenburg, the Sahlgrenska Hospital opened

in 1782 (founded in 1772 but only opened in 1782).

In Sweden, county hospitals have been called

"länslasarett", while other health care institutions

were called "sjukhus", such as Sabbatsberg Hospital

in Stockholm, Uppsala University Hospital,

Sahlgrenska Hospital in Gothenburg, and Malmö

General Hospital. The 1808 Army Field Medical

Regulations refer to the army's hospitals as

"sjukhus", not "lasarett".

In 1907, there were 75 hospitals in Sweden with a

total of 8,631 beds. In 1907, 79,372 patients had

been treated at these hospitals. Furthermore, at the

same time, there were 73 smaller hospitals and

infirmaries in towns and in countryside with a total

of 999 beds. In 1907, no county lacked hospitals,

most of them had several. The population of

Sweden in 1900 was 5,136,441.

The image to the left

shows an ongoing

treatment of a patient at

the Seraphim Hospital

(Serafimerlasarettet) in

Stockholm in 1898.

Because effective

treatment was often lacking, diseases that are now

easily treatable could often lead to death. Many

diseases were due to poor hygiene often combined

with large crowds. When soldiers were gathered

into armies, more soldiers usually died from

disease than from battles. This was because it was

not known how diseases were transmitted and in

what environment they thrived.

See also History of the Swedish Hospitals

Pharmacies (Apotek)

King Gustav Vasa (1496 - 1560) made the first

attempt to establish an orderly medical system in

Sweden. He acquired physicians and pharmacists

from abroad. The first pharmacy was licensed in

Stockholm in 1575. In 1675 there were 6

pharmacies in the city. In Swede, names of

pharmacies have traditionally been taken from the

fauna.

The image to the right

shows the interior of a

pharmacy in Linköping

at the beginning of the

1900s. Photo Hans

Högman, 2004.

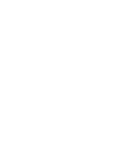

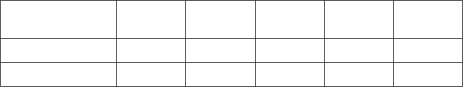

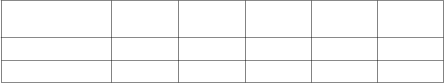

The following chart

shows the growth of pharmacies (Apotek) in

Sweden between 1700 and 1900.

Health Care and Diseases

in the Past (1)

Medical History - Medelpad

Medelpad is a province in central Sweden and its the

major city is Sundsvall.

There was no qualified medical care in Medelpad

before 1726, when Dietrich Theodorus Reineck, a field

surgeon, was employed as city surgeon in Sundsvall.

He was also skilled in the art of midwifery. However,

Reineck left already in 1731, dissatisfied with the

salary.

It was not until 12 years later, in 1743, that

Sundsvall's next city surgeon, Addeus Adde, who was

previously employed as a regimental field surgeon

with the Björneborg Regiment. He held this post until

1766 when his son Fredrik Adde took over as city

surgeon. Fredrik Adde held this post until 1775 when

he was appointed to a similar post in Hudiksvall

town.

In the city of Gävle, there had been a city surgeon

since the end of the 17th century. This post was held

by Carl Pelt between 1709 and 1743.

At this time, Adde and Pelt were the only trained

physicians in the northern half of Sweden, from

Gävle and north and down to Åbo on the Finnish side

of the Baltic Sea. After 1775, when Adde retired,

Gävle was again the nearest town where physicians

were available for the people in Medelpad province.

Carl Pelt settled down after 1743 as a mill owner at

Åvike mill in Medelpad. He had partly inherited the

mill from his father-in-law. He may well be regarded

as the first resident doctor in Medelpad.

Already in the "Medical Order" of 1668, it had been

decided that there should be a provincial physician in

every county of the realm.

The shortage of physicians in Norrland (northern

half of Sweden) had been raised during the

Parliament meeting in 1743 and it was then decided

that the "Senior Master at Härnösand Upper Secondary

School should always be a qualified physician". In 1744

physician Nils Gissler was appointed to this post as

"Provincial-Medicus for the Northern part of

Västernorrland County" which until 1762 included

provinces Gästrikland, Hälsingland, Jämtland,

Härjedalen, Medelpad, and Ångermanland. Gissler

was born in Torp parish in Medelpad.

Gissler organized a corps of assistants by teaching

the parish clerks (Swe: klockare) simple medical care

and bloodletting. It was also common at this time for

priests to have some medical training. Carl Pelt is

said to have been helpful to Gissler in organizing the

medical service in the county.

A few years after Gissler took office, Härnösand got

its first pharmacy. Sundsvall's first pharmacy was

established in 1763. This first pharmacy was called

"Gripen" (The Griffin). A second pharmacy was

opened in 1891 in Sundsvall, "Lejonet" (The Lion).

In 1839, a pharmacy branch was established in

Fränsta to serve the population of western

Medelpad.

When Västernorrland county was divided in 1762,

the county consisted of the provinces Medelpad,

Ångermanland, and Jämtland. Gissler was now

officially authorized as a provincial physician in

Medelpad and Ångermanland.

The city of Sundsvall hired Dr. J Sahlberg as city

physician in 1770, and the following year he was

appointed provincial physician for the whole of

Västernorrland when Gissler died.

Hospitals in Sundsvall

In 1776, during Sahlberg's time, a small hospital

was established in Sundsvall with 2 - 3 beds.

However, the hospital was closed in 1783 when

Sahlberg received Gissler's old lectureship at

Härnösand Upper Secondary School. The movable

assets were moved to Härnösand where a new

hospital was opened in 1788.

During the years of war 1808 - 1809, Sundsvall was

ordered to establish a field hospital. All available

space was used for the hospital. The situation in

Sundsvall was difficult as half the town had burnt

down a few years earlier (1803) and the town was far

from being rebuilt. The field hospital had the most

patients in the autumn of 1809 when over 800

wounded soldiers arrived from Västerbotten County.

Large numbers of soldiers were also stationed in

Sundsvall due to the city's strategic location. Among

these soldiers, field diseases were also rampant.

Some units were reduced by

half.

The image to the right shows

a hospital ward in the past.

Photo Hans Högman, 1998.

Medicinhistoriska museet,

Stockholm (Medical History

Museum).

It was not until 1 January 1844 that a permanent

hospital was opened in Sundsvall. The hospital

was located on Holmgatan and was a two-story

wooden building. The hospital was also an infirmary

for the venereal ill. Between 1861 and 1875, the

number of beds varied between 12 and 28, with a

total of about 80 patients treated per year.

During the 1800s, lumbering expanded considerably.

An exceptionally large amount of people migrated to

Sundsvall to look for jobs with the many lumber

firms in the region; sawmill laborers, loggers, log

drivers, and charcoal makers. The Sundsvall region

became a lumbering Klondike. Sundsvall became the

center of the world’s largest lumber industry district.

The flourishing of the sawmill industry in Sundsvall

during the second half of the 1800s increased the

pressure on the hospital and thus the need for

greater medical resources.

A new hospital was built in Norrmalm district in

Sundsvall in 1875. There was a capacity for 90 beds.

This three-story building was built of timber on a

stone base, contrary to the regulations of the

National Board of Health. The hospital now became

a county hospital.

In the 1880s, there were about 400 patients per year

and one physician. By 1890, the number of patients

had increased to 650 per year and an additional

physician's post was created. The Chief Physician at

this time was Adolf Christierin.

In 1890-1891 extensive improvements and repairs

were made to the hospital. The number of beds was

increased to 120 and electricity was installed in 1902.

In a 1902 inspection by the National Board of Health,

the hospital was described as: "a large wooden

building, poorly sound insulated, inflammable, difficult

to evacuate, and with bedbugs that could not be

eradicated."

In 1905, the construction of a new hospital began. It

was inaugurated on 6 March 1908 and was located

just east of the old operating theatre from the

beginning of the 20th century. The new hospital had

200 beds, 15 of which were for venereal diseases. By

1920 the number of beds had risen to 255. A new

maternity ward with 20 beds was opened in 1927.

In 1956, the number of beds in the hospital reached

714. The hospital remained here until 1975 when a

new hospital was completed in the Bosvedjan district

of Sundsvall.

Sundsvall's municipal administration then moved to

the old hospital buildings.

Since 1853, Sundsvall also had a water spa, located

approximately where the current Badhusparken is.

The town field surgeon's office from 1726 was

withdrawn in 1900 and the last "barber" in Sundsvall

was Bror Ulric Andersson. He is also said to have

been the last in Sweden.

Mental Health Care

In a detached building next to the hospital built in

1875, there was a care institution for the insane.

From the beginning, there were only two beds, in the

1890s six beds, and 1912 eight beds. In 1918, this

building was converted into a maternity ward, and

the mentally ill patients had to be transferred to

other places, including Frösö Mental Hospital.

In a news item in the Sundsvall newspaper, Nya

Samhället in 1910, a consultant from the Swedish

Poor-Law Association tells about a visit to Skön's

poor house. There 11 "fools" were kept, for whom no

more suitable place of residence could be prepared.

Gösta Sundqvist writes in his book "Everything was

not better formerly....." (page 32) "...have seen with my

own eyes these pitiful creatures in their wooden cages

on several occasions ....".

In 1943, the Sidsjön Mental Hospital was opened in

Sundsvall. From 1930, the government had taken

responsibility for the care of the mentally ill. The city

of Sundsvall also ran a municipal mental asylum

from 1916 at Västhagen Hospital. After 1967 it was

transferred to the county council to be used as a

nursing home.

Epidemics in Medelpad

Sundsvall is a seaport town and in maritime towns,

there was in the past always a risk of epidemics

breaking out. In 1812, Sundsvall also obtained the

right of staple towns (the right to trade directly with

foreign countries). This also increased the risk of

epidemics. But it was not only via ships arriving in

Sundsvall that disease could spread but also via the

Norwegian Atlantic coast. In the late 18th century,

peasants from Jämtland province transmitted

venereal diseases from Norwegian seaports.

Jämtland is a Swedish province located west of

Medelpad, by the Norwegian border.

Smallpox arrived in Sweden at the end of the Middle

Ages and an epidemic is known from 1528. Large

outbreaks occurred on and off in Sweden and

throughout Europe during the 18th and 19th

centuries. During an epidemic in 1753, three of Dr.

Gissler's children died. The first smallpox

inoculation in Västernorrland was carried out by Dr.

Gissler in 1761 on 20 children with successful results.

In 1785, a severe epidemic of dysentery ravaged the

whole of Norrland. In 1825, 1833, and 1858,

smallpox epidemics struck Medelpad. Protective

vaccination became compulsory in 1816. It became a

task mainly for parish clerks (klockare) and midwives.

In 1862 Sundsvall was hit by a diphtheria epidemic.

In 1831 a cholera epidemic was feared and a

quarantine master was appointed in Sundsvall. At

the end of the 1830s, a temporary quarantine station

was built on Tjuvholmen, an islet. The epidemic did

not occur in Sundsvall at that time, but in 1850s

cholera came in several rounds. In this epidemic,

about 50 people died.

In 1893, a decree was written that special infirmaries

were to be established in certain parishes as a

precaution against cholera. In Skön parish in

northern Sundsvall, a cholera barrack was set up at

Kabben along the old coastal road. In Granloholm

was Sundsvall's official cholera infirmary.

In the so-called. Petersén's house, west of the small

Büsowska woodland lake, Sundsvall's first epidemic

hospital was established in 1873. This house was

subsequently called the Smallpox House (Kopphuset).

The hospital remained here until 1909 when a new

epidemic hospital was completed on

Ludvigbergsvägen (the Ludvigberg road).

In 1908, when the new hospital was completed, it

was decided that the old hospital would be used by

the Medelpad Tuberculosis Society for the care of

tuberculosis patients. This wooden building was

moved in 1911 to the sanatorium area at Balders

Hage on the North Mountain (Norra Berget). The

building became a school much later. The

tuberculosis hospital had 100 beds. A children's

pavilion was opened in 1931.

According to statistics from the period 1895 - 1900,

various diseases of the respiratory organs were the

most common cause of death in Sundsvall.

In 1918, a severe influenza epidemic spread

throughout the world. It was the Spanish flu (The

Great Influenza epidemic). At the turn of June and July

1918, it arrived in Sweden. In 1919, 200,000 people

fell ill, but the death toll dropped to 9,000.

Sundsvall was also affected and in September 1918 it

reached its peak when 727 cases were reported.

Deaths occurred every day. There was no direct cure.

Food shortages during the Great War, malnutrition

(especially among the urban population), and

consequently low resistance contributed to the rapid

progression of the disease.

Symptoms of the Spanish flu included lower back

pain, high fever, sore throat, severe and rapidly

developing pneumonia, and even heart paralysis.

Many of the epidemics that struck the population

were largely due to poor hygiene and lack of

cleanliness. From 1874 onwards, street sweeping

was organized in Sundsvall. Initially, this task was

carried out by the town bailiff’s office, but from 1881

it was contracted out to a haulage contractor. The

removal of rubbish and latrine from the yards was

arranged so that the hauler was responsible for the

transport at the expense of the property owners. A

water barrel on wheels was also purchased for

watering the streets when the streets were swept.

By 1879, Sundsvall's water and sewage disposal

system had been developed. A few years later, in

1887, the first private water closets came into use.

Related Links

•

Diseases in the past

•

Swedish names of diseases in earlier times

•

History of the Swedish Hospitals

•

Poor Relief in the Past

•

Churching

Source References

•

"Svenska sjukdomsnamn i gångna tider" av

Gunnar Lagerkrantz, tredje upplagan 1988,

utgiven av Sveriges släktforskarförbund.

•

"Vår Svenska Historia" av Alf Åberg, fjärde

upplagan, 1978 (sid 319-321).

•

"Hembygdsforska! steg för steg" av Per

Clemensson och Per Andersson, 1990, (sid 123).

•

"Allt var inte bättre förr .....", Om hälsovård och

sjukvård i Medelpad efter 1700 av Gösta

Sundqvist, 1994

•

Skriften "Sundsvallsbygden" nr 15, årgång 14/97,

artikel "Historiska fakta och berättad

familjehistoria i Sundsvallsområdet" sid 21 av

Barbro Andersson.

•

Skräckens tid, farsoternas historia av Berndt

Tallerud, Prisma 1999.

•

Gamla tiders sjukdomsnamn, Olof Cronberg,

2018.

•

Wikipedia

•

NE, encyclopedia

Top of Page

Until 1970, Swedish pharmacies were run by

individual pharmacists, who had special privileges

from the Crown (so-called apoteksprivilegium), which

were hereditary but used to be transferred by

purchase (privilege trade). In 1970, the entire

pharmacy business was nationalized and

Apoteksbolaget (now Apoteket AB) took over the

business. The pharmacy monopoly ended in autumn

2009, and at the end of January 2010, most of the

pharmacies that were deregulated began to

rebrand.

Medical Treatments

Bloodletting

Bloodletting is an ancient medical treatment. Using a

so-called cup (Swe: “koppa”), blood was drained from

the body which would cause the sickness to come

out through the blood and thus cure the person.

Leeches were also used for bloodletting.

In the 1850s, the use of

bloodletting as a method of

treatment declined sharply.

The image to the right shows an

ongoing bloodletting in Värmland

in 1922. Image: Wikipedia.

Nordiska museet.

The image to the

left shows the

instrument (lancet)

with which one

opened the vein.

According to very ancient theories, the

body contained four fluids; blood,

mucus, yellow bile, and black bile. For good health,

these fluids had to be in balance with each other

and that disease occurred when any of these were

present in too small or large quantities. The theory

was based on the properties of drained blood. The

fluids were thought to reside in various organs of

the body, where they were formed and stored, and

added to the blood.

The yellow bile resided in the liver, the mucus in the

brain, the black bile in the spleen, and the red bile in

the blood. All fluids had to be present in the blood in

the right quantity and strength. It was mainly the

mucus that was thought to cause disease.

Regardless of the cause of a disease, bloodletting

was considered the best way to cure the sick person

by draining the diseased blood with its mucus from

the diseased area of the body.

Before the body's blood circulation was known, it

was thought that blood was locally bound in defined

areas and where blood could become bad from

mucus accumulation. Chills were thought to be a

way for the body to counteract this and that fever

prevented the mucus from congealing and so could

expel it through sweating.

Much superstition has been associated with

bloodletting. In ancient almanacs, there could be

precise instructions as to which part of the body,

ruled by different constellations in the Zodiac, was,

therefore, most appropriate, or inappropriate, to

draw blood from at a particular time for a particular

ailment.

Traits of the signature doctrine also came into play.

For example, bloodletting on young men would

preferably be done when there was a new moon,

while older men would be bloodletting when the

moon was on the wane.

The amount of blood to be drawn was depending on

the patient's age, size, health, and illness. According

to a medieval instruction: From a strong man should

be taken as much blood as a thirsty person can swallow

in one gulp. From a weak person, as much blood as

would fit in an ordinary egg.

It was most common to open veins in the arms.

There were three veins from which blood was

drawn. From the top vein, they would draw blood

partly for prevention and partly to cure headaches.

The middle vein was used to cure heart and lung

diseases. The lower vein was used to treat pain and

diseases of the liver, kidney, and spleen.

The Medical Thermometer

The medical thermometer and fever temperature

curves are aids in medical care. It was not until the

1870s that they came into regular use, mainly

through the German clinician Carl August

Wunderlich (1815 - 1877). By continuously

measuring body temperature, he was able to

establish that temperature curves had a different

appearance depending on the disease. Previously,

the fever had been thought to be a disease in its

own right. Now it was established that fever was

only a symptom, which was a great help in

diagnostics.

The physician Magnus Huss introduced the practice

of regularly measuring the temperatures of the sick

in 1838 at the Seraphim Hospital in Stockholm. It is

not known when medical thermometers began to be

used regularly in Sweden, but eight medical

thermometers were purchased in 1870 at the

Västerås Hospital.

The measurement of body temperature was greatly

simplified with the advent of min/max

thermometers. In Sweden, this happened in the

early 1880s. Swedish production of min/max

medical/clinical thermometers began in 1895.

Stethoscope

A stethoscope is an instrument that propagates

sound from a mouthpiece to the user's ears and can

be used to listen to the heart, lungs, and intestines,

among other things. The first stethoscope was

invented in 1816 by the French physician René

Laënnec and consisted of a

monophonic wooden tube. The first

version of a stethoscope consisted of a

wooden tube about 30 cm long with a

diameter of about 3-5 cm.

The image to the right shows a

wooden stethoscope from the late

19th century. Image: Wikipedia.

Anesthetics

When it comes to anesthetics, there wasn't much

available in the past. Ether was one of the first

anesthetics and began to be used as an inhaled

surgical anesthetic in 1846 in the US, followed the

following year by chloroform.

Ether is a clear, colorless, highly volatile, flammable

liquid with a peculiar aroma and burning taste.

Chloroform is one of the oldest anesthetics used in

surgery. It was considered to have several

advantages over the ether. It was not flammable like

ether and also has a more pleasant smell. However,

towards the end of the 19th century, it was realized

that chloroform tended to cause liver damage, as

well as cardiac arrhythmias and ether, became the

dominant anesthetic. The effect of chloroform is not

immediate; it takes at least five minutes for the

person to lose consciousness.

Anesthesiology is the study of anesthesia and

administering anesthetics. The word anesthesia is

not used very often in everyday Swedish, much

more common is the word narcosis (Swe: narkos)

and an anesthesiologist is usually referred to as a

“nakosläkare”. Anesthesia/narcosis means controlled

sedation together with painkillers.

Antisepsis

In the 1860s, antiseptics, i.e. cleanliness,

sterilization of surgical tools, etc., began to be used

in health care. An antiseptic is a germicide used on a

body surface to kill or inhibit the growth of

microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, parasites,

and viruses.

Phenol (carbolic acid) was used medically in the past

as a disinfectant in dilute solution, carbolic acid

solution, or carbolic water. When it was realized that

higher hygiene in childbirth was of paramount

importance, the risk of childbed fever decreased

significantly. In 1870, doctor Wilhelm Netzel at the

General Maternity Hospital (Allmänna

Barnbördshuset) in Stockholm was able to establish

that fever was spread by midwives and doctors

carrying organic substances on unclean instruments.

The hygienic procedures he introduced had a good

effect. In 1879, procedures were tightened and

midwives were required to wash their hands in a

solution of carbolic acid before performing

procedures.

In everyday language, antiseptics and disinfectants

are often used interchangeably. However,

disinfectants also include agents used to kill

microorganisms on objects such as tables, floors,

buildings, etc.

Antisepsis aims to combat pre-existing

microorganisms, as opposed to aseptic, which aims

to prevent the emergence of microorganisms, for

example through cleaning and sterilization.

X-Ray Examinations

An X-ray examination is an examination of the

body's bones or internal organs using X-rays. After

developing, any lesions or changes appear on the X-

ray photograph. In the past, the X-ray was also called

radiography and the plates radiogram. Wilhelm

Conrad Röntgen (1845 - 1923) was a German

physicist and the discoverer of X-rays.

X-rays began to be used after 1895.

History of the Penicillin

The Egyptians used mold from bread or porridge as

an antibiotic thousand years ago. In the Swedish

peasant's practice, poultice (Swe: grötomslag) are

listed and if one was left on for a long time, it began

to mold.

A poultice, also called a cataplasm, is a soft moist

mass, often heated and medicated, that is spread on

a cloth and placed over the skin to treat an aching,

inflamed or painful part of the body. It can be used

on wounds such as cuts. The Swedish word

“grötomslag” literally means “porridge wrapping”.

What the porridge is made of is of no great

importance, it can be prepared from ordinary flour,

oatmeal, linseed, or something similar, the

important thing is that it maintains a suitable

temperature to heat without burning or causing any

other discomfort. When the porridge is ready, it is

placed in a cloth folded into a package so that it

does not stick, then the package is placed on the

area in question.

In 1928, Alexander Fleming (1881-1955) discovered

that the mold fungus Penicillium notatum produced a

bactericidal substance. He called it penicillin. In

1939, Ernst Boris Chain and Howard Walter Florey

began experiments to produce large quantities of

penicillin from broth cultures. Its bactericidal effect

was confirmed in large clinical tests in 1942. Mass

production soon began in the US and saved the lives

of tens of thousands of Allied soldiers during World

War II.

The first treatment with penicillin in Sweden took

place at Sabbatsberg Hospital in 1944.

Antibiotics:

Antibiotic means to biologists substances produced

by living organisms for the purpose of keeping other

organisms away. For example, both bacteria and

fungi live either as parasites or by breaking down

dead material. Since both have the same food

source, they try to poison each other by secreting

substances that the other cannot tolerate. For

example, ascomycetous fungi produce penicillin to

keep bacteria at bay, while actinobacteria produce

amphotericin to keep fungi at bay.

The antibiotics that have become known are those

that can be used as medicines. When we talk about

antibiotics in everyday language, we are referring to

drugs against bacteria in general. The drugs can be

either bactericidal (killing) or bacteriostatic

(inhibiting growth).

The first antibacterial drug was mercury, used

against syphilis as early as the 16th century.

However, this was very dangerous for the patient.

In folk medicine, mold has been used since ancient

times as a remedy for various diseases. The first

scientific observation of antagonism between

different microorganisms was made by Louis

Pasteur (1822-1895) and Joubert, who already in

1877 observed that certain aerobic bacteria

inhibited the growth of anthrax bacteria.

Dental Care

Since 1797, a degree has been a requirement for

practicing dentistry in Sweden. Organized dentistry

also began to appear in the 19th century.

Dental care has been available for a long time

through barbers. But now came trained dentists.

However, it was expensive to go to the dentist and it

was a "pleasure" for the wealthy. The anesthetic used

was alcohol. The dental drills used in the late 19th

century were treadle-driven. Only after the turn of

the century did the first electrically powered drills

appear. There were also traveling dentists around

the turn of the century. The first Swedish school

dental clinic was established in Stockholm in 1907.

Folktandvården (Public dental care) is the name

given to the public dental care in Sweden that has

been run by the county councils (Landsting) since

1938. Initially, Folktandvården only provided dental

care for children, but over the years it has expanded

to include both adult and specialist dental care.

Number of Swedish Pharmacies 1700 - 1900

Pharmacies

1700

1750

1800

1850

1900

Stockholm

9

9

12

14

20

Entire country

27

45

95

137

322