Copyright © Hans Högman 2021-09-22

Poor Relief in Sweden Formerly

Introduction

Poor relief (Swe: fattigvård) was the old-fashioned

care provided by society for poor people who could

not support themselves. The very poorest were

housed in the parish poorhouse, (Swe:

fattighus/fattigstuga), where children, the elderly,

and disabled paupers were cared for, but also had

to take care of each other.

“Rotegång”, or roaming, was a system of providing

for the very poorest in peasant society. Those

paupers who could not be placed in poorhouses

were assigned to a “rotegång”. The pauper had to

walk between the farms according to a set order.

These paupers (rotehjon) were expected to help out

and do right by each other. “Rotegång” literally

means “walk the parish districts” (rote = district).

A translation such as “transient parish paupers”

might work in English.

It was those of the destitute paupers who could not

be placed in a poorhouse that were referred to the

rotegång. The Homesteads in rural parishes were

traditionally divided into districts called rote. A

village rote (district) consisted usually of six

homesteads. Each rote was responsible for one

pauper and the paupers were shifted between the

homesteads according to a schedule: typically the

pauper stayed on each homestead for a few days

up to a week at a time. They were expected to

contribute with what they could in exchange for

food, care, and housing.

The Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, the Church was responsible for

the care of the poor, but individuals were also

obliged to show concern for the poor. Helping the

poor was a good deed, and good deeds showed

that people had repented of their sins and wanted

to mend their ways.

Poverty was not a disgrace but a misfortune

suffered, which, like many other things, was due to

God's will. After death, the rich had more to answer

for before God than the poor. Wealth gave more

opportunities to do good, and those who did not

take advantage of this opportunity had to atone for

it after death. The poor had fewer opportunities to

help others and thus less responsibility.

In the Middle Ages, the combined old people's

homes, poorhouses, and hospitals run by the Order

of the Holy Spirit (Helige Andes Orden) were called

“Helgeandshus” in Swedish, which was an

important part of the care system of the time. The

Helgeandshus (Helgeandshuset) in Stockholm was

located on a small island called Helgeandsholmen.

The building remained standing until around 1604

and gave the island its name "Helgeandsholmen".

With the Reformation in the 16th century, this way

of thinking changed and wealth was now seen as a

sign of God's grace. Poverty, on the other hand, was

seen as a personal failure, but it was several

hundred years before poverty was seen as a social

problem.

Hospitalen

The oldest institutions for the care of the poor,

apart from those associated with monasteries,

were hospitalen, which were a combination of

institutions for the sick and the poor.

Already in the Middle Ages, these were financed by

donations, and after the Reformation, they

continued to exist through the hospitalen. Larger

towns and dioceses had these “hospital”

institutions.

The hospitalet in Gothenburg, which was

inaugurated in 1627, was administered by the city

administration and had no ecclesiastical foundation

at the bottom.

The Hospital Ordinance of 1624 is Sweden's first

poor-law ordinance. Under the decree, all those

unable to work were to be admitted to a “hospital”,

except for children who were to be admitted to an

orphanage. In the beginning, orphanages were only

established in Stockholm.

Allmänna Barnhuset (The General Orphanage) in

Stockholm was an institution for children. Between

1633 and 1885, the orphanage, which until 1785

was called Stora Barnhuset (The Great Orphanage),

was located on the crossroads

Drottninggatan/Barnhusgatan in what is now the

Barnhuset block. It moved in 1885 to Norrtullsgatan

where it operated until 1922.

Between 1880 and 1922, some 20,000 children

were enrolled at the General Orphanage. If the

mother was unable to pay for the maintenance of

the enrolled child, she could leave it free of charge

in exchange for living at the Children's Home for

eight months and nursing her own and one other

child. In addition, she would participate in the daily

work of the Children's Home/Orphanage.

Under the 1626 Chancery Regulations, the Royal

Chancery, which in 1635 became the Central Office

of the Chancellery (Kanslikollegium), was to oversee

the hospitals, houses of correction, and

orphanages.

According to the Poor Law Ordinance of 1642, the

hospitalen were to admit the poor and sick who had

no relatives who could support them, as well as

people with contagious diseases.

The City of Skara had this type of hospital in the

17th century, as can be seen from the cathedral

chapter's record of admissions.

In 1686, the Ulricae Eleonorae Hospital Foundation

built the so-called Queen's House (Drottninghuset)

in Stockholm for destitute women.

The city of Stockholm was the first to establish

poorhouses. A poorhouse was built at

Sabbatsberg in 1751 on behalf of Stockholm's

Grand parish (Storkyrkoförsamlingen), and a medical

spring institution was started there in 1764, and a

medical spring hospital in 1807.

Those admitted to the hospitalen were poor old

people, especially elderly single women, the sick,

and the disabled, as anyone who could physically

work did so. The labor shortage was an unknown

concept in the old agricultural society, where there

was more heavy work to do than there were people

to do it, as almost all work was done by manual

labor.

The connection between poor relief and health care

was therefore quite natural before the 1760s.

However, in the 1763 hospital regulations, the

poor relief was separated from the hospitalen. In

the latter part of the 18th century, the care of the

sick was transferred to the hospitals (sjukhus), and

only the mentally ill were admitted to the

hospitalen (mental hospitals).

Poorhouses (Fattighus)

According to the Poor Law of 1642, each parish

had to establish a poorhouse. This requirement

was reiterated in the 1686 Church Act, but it was

not until the 18th century that poorhouses began

to be set up to some extent. The oldest

poorhouses, were located next to the church so

that parishioners could bring gifts (alms) to the

poor while visiting the church.

It was only in the 19th and 20th centuries that

poorhouses (fattighus/fattigstuga), which from 1918

were called old people's homes (ålderdomshem),

was built on the outskirts as if ashamed of the

phenomenon.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, many towns in

Sweden established poorhouses and a directorate

for the poor relief, but otherwise, the poor relief

was looked after by the city administration. Some

rural parishes also set up a directorate for the poor

relief, but as a rule, the parish council

(sockenstämman) handled most of the day-to-day

poor relief (fattigvården).

Poor care through poorhouses is also known as

indoor relief.

The image to the right shows the poorhouse in

Turinge socken (parish), Nykvarn, at the beginning

of the 1900s. Photo: Photographer unknown, about

1903 - 1910. Turinge-Taxinge local history society.

ID:

se_ab_tthf_0030.

PDM.

The poorhouse

was built in 1780

after the owner of

Vidbynäs manor,

Major Carl Gustaf

Elgenstierna,

donated land and the owner of Nykvarns Works,

Major Axel Tham, donated funds and materials. The

poorhouse consisted of three rooms, an office, and

a spacious attic and was built of brick. The

poorhouse was then in use for the parish's poor

until October 1921.

The parishes (socken) were slow to establish

poorhouses, as the peasants preferred a

combination of a system of boarding and boarding-

out (often in the form of poor relief auctions) of the

paupers and “rotegång”, which meant that the

paupers (rotehjon) walked or were taken between

the farms within the parish district (rote). The rote

paupers were thus dependent on board and

lodging with the parish farmers, in turn for a few

days in each farm.

The paupers (fattighjon) were first and foremost

those who were unfit for work (crippled), such as

the physically or mentally disabled, the terminally

ill, the elderly, and children without relatives to care

for them. The motley crew of paupers also included

the impoverished (without means) who received

poor relief from the parish.

The poorhouses were funded by fees. During the

19th century, most of the poor were found in the

cities, and they were often so-called house-poor

(husfattiga), i.e. they had a place to live in but could

not support themselves. It was therefore more

common to provide food, clothing, and a small

amount of money;

only in cases of

extreme need

were people

placed in

poorhouses.

The image to the

right shows the

poorhouse in

Gärdserum, Östergötland. Kalmar Läns Museum.

ID: KLMF.Gärdserum00001.

In 1829 there were 1,279 poorhouses, which were

located in about half of the country's parishes.

Small parishes felt they could not afford poor relief.

In a survey of the poor relief in Sweden in 1829,

there is a summary of the size of the poorhouses.

Most poorhouses were between 20 and 60 square

meters. In 1829, a total of 5,987 paupers lived in

1,084 poorhouses, which means an average of 5.5

paupers per poorhouse. According to statistics

based on 335 parishes, women constituted a clear

majority of the paupers, as much as 78%.

If the husband died, the income ceased. Women's

ability to support themselves and their children was

severely limited at this time. Children, the elderly,

the disabled, and the sick were all mixed in the

poorhouses.

As a rule, the poorhouses were built of lumber.

Existing buildings were also sometimes converted

into poorhouses. Usually, they had one or more

rooms, one of which served as a kitchen. The

paupers kept their few belongings in chests, usually

under the bed.

In 1869, i.e. at the end of the three great years of

famine 1867 - 1869, a dismal record was broken in

the care of the poor. At that time there were

217,373 registered paupers in the country. At that

time, Sweden had a population of about 3.5 million,

which means that paupers accounted for just over

6%.

The years of famine between 1867 and 1869 had a

major impact on the issue of poor relief. However,

not in the sense that care became more generous.

At the Parliament meeting of 1869, many argued

that compulsory poor relief should be reduced to a

minimum. The distress of the last decade had been

too costly for the parishes. The Poor Law of 1871

also implied a tightening of the poor relief.

In 1737, the parishes in Stockholm were given

responsibility for running poorhouses. Stockholm's

parishes then joined forces to organize a poor

relief. In 1751, the city parishes in Stockholm jointly

bought Sabbatsberg for this purpose. The activities

of the Klara poorhouse were moved to Sabbatsberg

the same year. The Nicolai poorhouse was

completed in 1756 and could accommodate 300

paupers. The Kungsholm poorhouse at

Hantverkargatan 8 was built in 1762. It was closed

in 1872 when it was moved to Sabbatsberg.

The image shows a room at the Sabbatsberg care

and old people's home in Stockholm in 1896.

Photographer unknown. ID: Stockholms stadsarkiv

SE/SSA/0053/Sabbatsbergs vård- och

ålderdomshem/F9:1. Stockholmskällan.

In 1862, the City of Stockholm took over full

responsibility for the poor from the parishes. The

city's poor care, except that on Södermalm district,

was to be transferred to Sabbatsberg. The 360

places were then increased by another 525. The

various poorhouses on Sabbatsberg were named

after the parishes they served, such as Adolf

Fredrikhuset and Johanneshuset, located nearest to

Vasaparken.

With the 1918 Poor Relief Act, the poorhouses

were renamed old people's homes (ålderdomshem).

Paupers (Fattighjon)

A pauper (fattighjon) was defined as a person who

benefited from the parish's poor relief.

In the Middle Ages, people who could not support

themselves were referred to the poor relief

provided by the peasants of the parish in the form

of board and lodging, in turn for a few days on each

farm (rotehjon).

The paupers were first and foremost those who

were unfit for work (crippled), such as the physically

or mentally disabled, the terminally ill, the elderly,

and children without relatives to care for them. The

paupers also included the impoverished (without

means) who received poor relief from the parish.

Poor relief, in the form of “rotegång” for paupers

(rotehjon), was prohibited by the 1918 Poor Law, but

from the 16th century had gradually begun to be

replaced by poorhouses and the housing of

paupers (inhysehjon) - dependent tenants -, one

year at a time, at the expense of the parish poor

fund.

The image shows poor children from Jeppetorp

poorhouse,

Grythyttan, 1913. Four

barefoot boys in worn

clothes. Unknown

photographer.

Nordiska museet. ID:

NMA.0033630.

Digitaltmuseum. PDM.

Workhouses

In the 18th century, so-called workhouses (Swe:

arbetshus) were set up in major cities to provide

useful training and employment for the

unemployed. In the countryside, there were hardly

any unemployed people, but a young man who was

unwilling or unable to work in agriculture, forestry,

or any other local activity could be sent to a

workhouse in the county seat.

Workhouses could be combined with a hospital;

Karlskrona had a hospital and a work department

1794-1806. On 28 May 1813, a royal circular was

issued to the county governors to try to encourage

the establishment of workhouses, i.e. arbetshus.

There were several workhouses in Stockholm. The

Voluntary Workhouse was located on Södermalm in

Katarina Parish from 1773 to 1844 and continued

as the General Workhouse from 1844 to 1860 and as

a workhouse institution until 1925. From 1926 it

was called the Högalid Care Home. There was also a

voluntary workhouse on the north side of

Stockholm between 1797 and 1880. In Uppsala,

there was a workhouse in the mid-19th century.

Poor care through workhouses is also known as

outdoor relief.

Charitable Institutions

Charitable institutions (Försörjningsinrättningar)

were institutions for the care and housing of the

poor. In Stockholm, there were several such

institutions with different “guests”. The General

Charitable Institution for Women in Stockholm (called

Grubbens) existed between 1860 and 1926 and

was transformed into St. Erik's Hospital in 1926.

Gothenburg had a large charitable institution and

workhouse from 1855. In 1888, the even larger

welfare charitable institution called Sjuk och

vårdhemmet Gibraltar was completed. In the 1930s

it had 1,663 beds for the mentally ill, the physically

ill, the tuberculosis patients. Charitable institutions

were also established in rural areas at the end of

the 19th century.

Work Homes (Arbetshem)

The 1918 Poor Law required the county councils

(Landsting) and the cities not being part of a county

council, i.e. the larger cities, to establish special

work homes for persons over 18 years of age

who were somewhat able to work and needed

institutional care but were not suitable for old

people's homes, charitable homes or nursing

homes. Work homes (arbetshem) were also used for

people with maintenance liability who had been

ordered to work under the Poor Law, i.e. those who

had been placed in workhouses during the 19th

century (as opposed to forced labor institutions

where convicts were placed).

Rotegång - Transient Parish Paupers

"Rotegång", or roaming (kringgång), was a system

of providing for the very poorest in peasant

society. Already in the Middle Ages, a form of

rotation system was used for the non-able-bodied

poor in the Swedish countryside, where there were

no poorhouses and helgeandshus (combined old

people's homes, poorhouses, and hospitals) as in

the cities.

The paupers who could not be placed in

poorhouses received care in the form of “rotegång”.

The pauper (called rotehjon - transient parish

pauper) was then allowed to move between the

farms according to a set order. Several farms -

usually six - attached to a so-called “rote” district

had a joint obligation to provide food and lodging,

and to some extent care for the pauper. The

pauper was expected to help out and do right. As

proof of his entitlement, the pauper carried a so-

called “poor hammer” made of wood. On the

hammer was written the order of rotation and the

length of stay on the farms.

There were at least two practices for “rotegång”.

One was based on the mantal-set value of each

farm or homestead in which system the number of

days the pauper stayed in each homestead

depended on the property tax code. The pauper

then stayed more days on a profitable farm than on

a less wealthy farm.

In the other system, the

pauper stayed the same

number of days on each

farm.

The image to the right shows

“rotehjon” (pauper) Tåars-

Johan, Sätuna parish’s last

transient parish pauper

(Falköping). Photo: Gustaf

Holm circa 1890.

Västergötlands museum. ID:

1M16-A145156:311. PDM.

“Rotegång” for children was banned in 1847. Poor

auctions became more common for children.

“rotegång” as well as the poor auctions were finally

banned in Sweden in 1918.

The rotegång paupers (rotehjon) were the poorest of

the poor since they, unlike the dependent tenants

(inhyseshjon), were confined to rotegång which

meant that they received the necessary food and

lodging in one farm after another, with a fixed

number of days on each farm. Many parishes were

divided into rote districts, with one or a few villages

per rote, which were jointly responsible for the

paupers assigned to them by the parish council.

It was considered bad luck to have a dying rotehjon

in the home. Therefore, it was common for them to

be passed around between households even while

they were dying. This rotegång was also called dung

(dynga) and the poor, who in this way moved from

farm to farm, dung pauper (dyngenhjon).

Poor Hammer / Beggar’s Hammer

A poor hammer (fattigklubba), also known as a

beggar's hammer, was a symbol made of wood to

show that the bearer was poor and in need of a

livelihood according to a fixed parish lap based on

the rotegång system (see above).

A pauper could be granted rotegång and become a

so-called rotehjon (rote pauper), which meant that

he had to go to the farm that was next in line in the

rote district for food and lodging, which usually was

the farm where the poor hammer was. Otherwise,

he had to bring his poor hammer and a notebook

in which the time and place were recorded. They

had to stay for one to five days depending on the

mantal-set value (tax code) of the farm. When the

time was up, he had to go to the next farm in the

rote district. Those who were able had to walk

between farms, while frail paupers were sent with

horse and carriage.

The poor hammer usually had carved owner’s

marks for the farms in the rote district that was

obliged to participate in the

maintenance of a rotehjon. The

pauper had to walk between the

farms according to a set order. So,

on the hammer was also this order

noted and how long a stay on each

farm could last.

The image shows a poor hammer

(fattigklubba) from Hälsingland

province, Sweden. Image:

Wikipedia.

Dependent tenants (Inhyseshjon)

Inhyseshjon and all others who lived or were

housed in someone else's home or on someone

else's land without being in his service were

categorized as dependent tenants or dependent

lodgers. They were usually poor people, paupers,

placed by the parish council with a family for a

fee, because they were unable to work. There were

elderly people, orphans, and disabled people who

were housed at the parish's expense, thus escaping

the rotehjon's rote migration (rotegång). They

contributed as much labor as they were able and

were placed in the family that demanded the

lowest remuneration in a poor auction.

Poor Relief in the Past

Poor Auctions

Poor care auction, poor auction, sale by auction,

etc., was an old form of poor care in Sweden that

involved auctioning off paupers to the lowest

bidder, i.e. to the person who demanded the least

compensation from the parish or municipal poor

relief board for taking care of a pauper. Poor

auctions are best known for the auctioning off of

children, i.e. children's auctions, but the method was

actually used for paupers of all ages, except for

particularly old children.

The poor were divided into two classes. The first-

class of paupers included those who were unfit for

work, disabled, such as the physically or mentally

disabled, the terminally ill, the elderly, and children,

who had no relatives able or willing to care for them.

Second-class paupers included those who received

temporary poor relief from the Poor Relief Board.

According to the law, paupers were to be placed in

poorhouses in the first place. In the second instance,

the Poor Relief Board was obliged to pay for their

board, lodging, and support. Some parishes could

not afford to build a poorhouse, while others refused

to pay for one.

Rotegång and poor auctions were preferred as a

cheaper alternative to building a poorhouse. This

also meant that paupers could be used as labor.

Every year a placard with the names of the first class

of paupers was published in a notice in the parish

church. On the last Sunday before Christmas, the

poor auction was held in the parish courthouse after

the sermon. The Poor Relief Board auctioned the

pauper to the parishioners, who bid during the

auction on the compensation they required from the

Poor Relief Board for caring for the pauper for a

year. The person who offered to take care of the

pauper for the lowest compensation won the bid.

The Poor Relief Board reimbursed the bid winner for

food, lodging, clothing, and any medical care and

funeral expenses. At the same time, the pauper was

expected to work for the bidder to the best of his

ability. This auction was then repeated at the end of

the one-year period.

There are many accounts of how the paupers, often

children, were mistreated and abused and exploited

as cheap labor.

Defenseless/Vagrants

Being unemployed was considered a crime and

implied immediate punishment in the form of penal

servitude. This statute was instituted in 1664 and

was practiced until 1926 except for some revisions.

Thus, it was a crime to be poor and drift about

(vagrancy), i.e. to be unemployed.

You were then considered defenseless (försvarslös)

and could be sentenced to penal servitude

(straffarbete) in a house of correction. The 1885

vagrancy law decriminalized vagrancy (lösdriveri),

and vagrants could instead be sentenced to forced

labor (tvångsarbete), which society now regarded as a

treatment rather than a punishment. You were then

defenseless and could be taken out for forced labor

or active military service (krigstjänst).

Under the 1885 Act, vagrancy meant "failure to make

an honest living" and included those who were

"roaming about the country". A vagrant was "a person

who has no permanent abode, permanent employment,

means of livelihood, and who moves from place to

place, supporting himself by casual labor, begging and

similar, tramp, vagabond, hobo". Under the 1885 Act,

vagrants could be sentenced to forced labor.

The Crown Labor Corps (Kronoarbetskåren) was a

government hard labor institution that, among other

things, took in able-bodied defenseless persons from

prisons.

Poor Box

A poor box was a money box for alms to the poor

and sick and was often set up at

churches.

The image to the right shows a

poor box at Rättvik church,

Dalarna.

Image: Wikipedia.

The following writing is on the

board:

Ps 41:2

Säll är then som låter sig

wårda om then fattiga : ho-

nom skal HERREN hjelpa

i then onda tiden.

Blessed is he who cares for the poor:

the LORD will help him in the time of trouble.

II Cor. 9:7.

Hwar och en som han sielf

wil; icke med olust, eller af

twång. ty en galdan gif-

ware älskar GUD.

Each one must give as he has decided in his heart,

not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a

cheerful giver.

Poor-Laws

According to older ordinances, parishes and towns

were asked to give alms to the poor and to build

poorhouses. These guidelines were drawn up by the

government in 1624 in the so-called Hospital

Ordinance (hospitalsförordningen) and were in force

until 1763.

In 1763, the first Poor Relief Ordinance was passed,

which established the obligation of each parish to

care for those of its citizens who were in need. In the

latter part of the 18th century, the concept of

domicile was also introduced, which meant that the

poor could only be helped by the parish in which

they were born.

However, no rights were given to the poor to claim

poor relief until 1847 by the ordinance issued that

year. This ordinance laid down certain basic

principles for the organization of poor relief.

However, the parishes were allowed to organize the

poor relief according to the conditions appropriate to

the locality.

According to the 1847 Poor Law Ordinance, a Poor

Relief Board (fattigvårdsstyrelse) was to be established

in each parish. The Ordinance laid down certain local

obligations and prohibited begging throughout the

country.

The parish committee, established in 1844, could

also function as a poor relief board. A parishioner

was entitled to poor relief after three years'

residence in the parish without receiving poor

relief, and the parish council could no longer refuse

people from moving to the parish, as it could under

the 1788 ordinance, if it was feared that an old or

less able-bodied person would be a burden on the

poor relief system.

On the other hand, the parish could refuse poor

relief if the person did not have the right of domicile

(hemortsrätt). Previously, this right had been obtained

through domicile registration. Long-running disputes

over domicile registration

(mantalsskrivning/kyrkoskrivning) were common in the

early 19th century. Anyone who was registered as a

domicile of the parish was then entitled to poor

relief.

Such disputes, as well as disputes between the

parishes in poverty matters, went to the County

Governor (Landshövdingen) for decision - a precursor

to the later County Court (länsrätten) - and could also

go up to the Kammarkollegium (The national judicial

board for public lands and funds) in Stockholm.

In 1871, a new law was passed concerning the poor

relief, based on the 1847 ordinance, with the

difference that the 1871 law significantly restricted

the right of the needy to assistance. The 1871 Act

remained in force until 1918 when a more up-to-date

law was passed on the subject.

In 1853, a new ordinance was introduced that was

relatively generous and allowed individuals to appeal

to the County Administrative Board (Länsstyrelsen).

In 1863, when the municipalities were formed and

replaced the former secular parishes (socken), the

municipal committee (kommunalnämnden) was

responsible for the care of the poor, unless a special

poor relief board (fattigvårdsstyrelse ) was appointed,

and this did not become compulsory until 1919.

In small rural municipalities (landskommuner), poor

relief was the main task of the municipal committee,

and old records show that it was not just a matter of

passively alleviating the worst of the hardships, but

that more constructive help was also given.

The 1871 Poor Law tightened up the provisions of

1847 and the subsequent ordinance of 13 July 1853,

among other things by making it impossible to

appeal against the decision of the municipal

committee on poor care. The right of appeal to the

County Administrative Board was reintroduced by

the 1918 Poor Law Ordinance.

The 1918 Poor Law reformed the system, and each

municipal administration became a poor care

community. The Act was adopted by the Swedish

Parliament on 14 June 1918 and remained in force

until 1955. It humanized the poor care system in

Sweden at the time and represented a transition

between the old-style poor care system and the

more modern social welfare system.

Among other things, poor auctions and “rotegång”

were banned, and the poorhouses became old

people's homes instead (ålderdomshem), and the

right of appeal was reintroduced as mentioned

above.

The image shows Tystberga old people's home and

poorhouse in 1929. Image: Södermanland Museum.

Poor relief, in the form of “rotegång” for paupers, was

thus banned in 1918 after having been banned for

children in 1847.

In the 1918 Poor Law, the concept of the poor and

his position in society differs considerably from that

of the 1871 law.

The introduction to the 1871 Act states that the poor

relief is "a gift of mercy, which the poor cannot insist

on", i.e. the poor should be satisfied with the help he

or she received.

The 1918 law goes in the opposite direction, now

emphasizing that the care of the poor is "the

obligation of society towards the poor". The view of the

poor in the 1871 Act is rather harsh and indifferent,

whereas the 1918 Act has a softer view of the poor

for the time and expresses the idea that "even the

poor have certain rights, which he can claim".

In 1937, each municipality was obliged to keep a

register of the relief activities in the municipality, i.e.

the municipality was obliged to document its poor

relief activities.

In rural municipalities with a municipal office, the

latter could keep the register and the responsibility

then lay with the municipal committee, otherwise, it

was the poor relief board that had the responsibility,

but from 1957 it became the social welfare board

(socialnämnden).

Child welfare committees (barnavårdsnämnd)

became compulsory in 1926. It was then possible to

appoint a three-member committee, which was a

combination of a child welfare board and a poor

relief board.

Government Supervision

The care of the poor was the parish's business,

from the beginning based on the old parish loyalty,

when, of course, one took care of the "children of the

parish" who had fallen on hard times.

However, parish loyalty did not last in the face of the

developments of the 19th century. The labor force

became more mobile and the more people who lived

from wage labor outside agriculture, the greater the

risk of poverty caused by unemployment and not just

by illness or old age as had been the case in the past.

The government's intervention in the care of the

poor was at first restricted to the laws and

regulations on the care of the poor. The Government

Inspector for Care of the Poor (fattigvårdsinspektör),

attached to the National Board of Health and

Welfare (Socialstyrelsen), which had been

established in 1912, was added by the 1918 Poor

Law. The title was changed by the 1924 Child Welfare

Act to Government Inspector of Poor Care and Child

Welfare, who directed the work of the poor care and

child welfare consultants. Under the 1918 Poor Law,

the County Administrative Board (Länstyrelsen) was to

supervise that municipalities provided poor services

in accordance with the law. In this task, the County

Administrative Board was to be assisted by a poor

care consultant (fattigvårdskonsulent).

No special training was required for the old parish

poor care. It is only when government supervision is

introduced that training becomes relevant. The first

social work training was established in Stockholm in

1921 and developed into the Social Pedagogical

Institute (Socialpedagogiska Institutet). Training in

Gothenburg was added in 1944, in Lund in 1947, and

in Umeå in 1962. These Social Institutes were run by

municipalities. In 1963, the Social Institutes were

nationalized and renamed as Social Colleges. The

Social Colleges were established in Örebro in 1976

and Östersund in 1971.

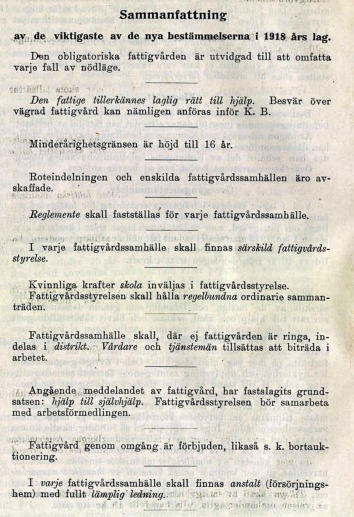

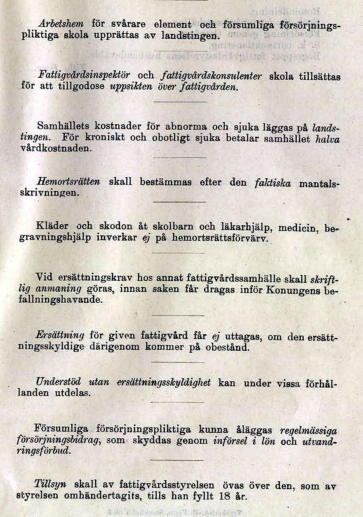

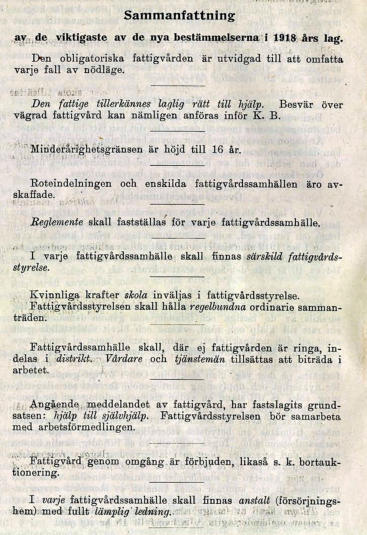

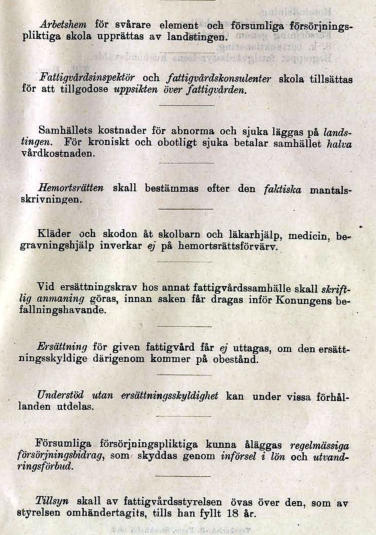

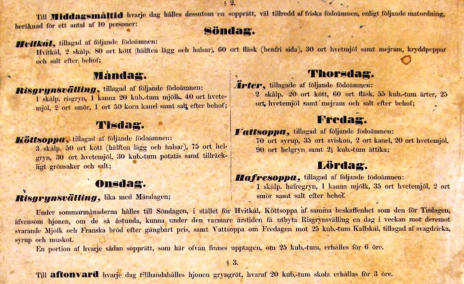

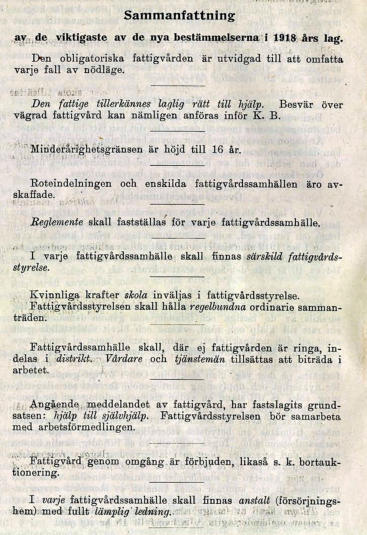

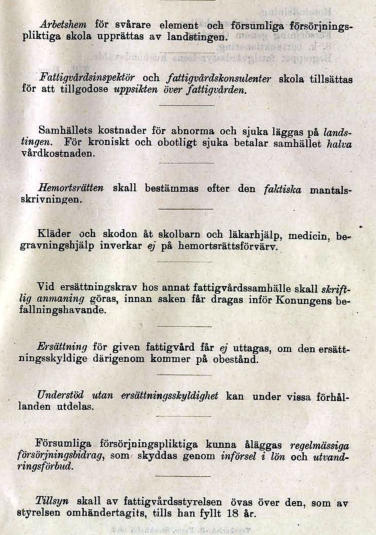

Summary of the 1918 Poor-Law

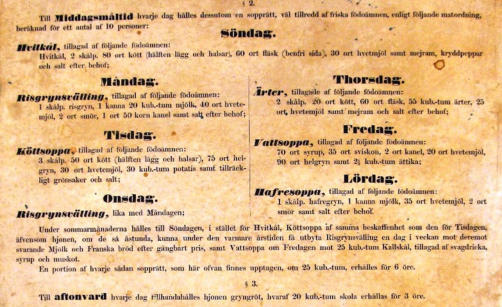

Menu at Sabbatsberg Poorhouse 1866

For the midday meal each day there is also a soup

dish, well prepared from healthy foods.

•

Sunday- Cabbage soap

•

Monday – Rice gruel

•

Tuesday – Meat broth

•

Wednesday - Rice gruel

•

Thursday – Yellow pea soap

•

Friday - Rice gruel

•

Saturday – Oatmeal gruel

Source: Menu at Sabbatsberg Poorhouse in

Stockholm in 1866. Stockholms stadsarkiv

SE/SSA/0053/ Sabbatsbergs vård- och ålderdomshem,

ämnesordnade handlingar F10, volym 1.

Stockholmskällan.